|

| What does SHE think? |

That question is instantly joined by another: Why do I read? Then there is, of course, What else could or should I be doing? And right away we can discount Sunny Juliet’s opinion, since hers is a distinctly self-serving perspective. In her point of view (I cannot imagine I’m misreading her on this), all the hours I’m focused on objects held in my hands is robbing her of my attention, and there’s no amusement for her in watching me, either, as what I am “doing” seems so little like doing anything.

Oh, my dear, impatient, so patient companion!

|

| Even with a beef bone, she hopes for play with momma. |

What do I seek in all this reading? That’s the “why” question. One answer is understanding. I want to understand as much as I can of the knottiest, most insoluble human predicaments, problems to which I will never have a full answer as long as I live. That answer surely elicits another “Why?” What is the good of understanding that leads no further?

Oh, tree in the garden! What knowledge did its fruit offer?

I see different kinds of hungers for knowledge and understanding in different human beings. The pragmatically scientific want to take things apart, see how they work, and then do things that have not been done before. They are eager to change the world. Why? Sometimes for the betterment of mankind, sometimes just “Because we can.” Around those seekers, always, are hangers-on and parasites with no intrinsic hunger of their own for the knowledge and inventions, who do, however, care very much for the wealth that can be generated, wealth multiplying itself into the future, if only one makes a reservation early enough on the investment bandwagon. Theirs is hunger for accumulation, which is qualitatively different from hunger for knowledge.

And yet, honestly, don't most of us have a certain hunger for accumulation? I look around my life and see art on walls, books on shelves, stacks of photograph albums, dishes of stones and fossils, and physical representations of beautiful living things.

Beauty and memories, memories and beauty. Objects that invite my eyes and my hands, pages that carry me over oceans to inhabit other lives and other times and also let me relive my own past years. Associations carried by these material objects are my real accumulated wealth, the objects themselves only carriers.

Does the quest for understanding life look more to the past than to the future? “Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards,” wrote Kierkegaard. We do seek hope in the possibility of applying our understanding to the future. For example, restricting the question of “how we came to be where we are” to immediate family and acquaintance rather than society as a whole, I can see errors I have made and try to avoid repeating them in what remains of my time on earth. Sadly, human societies, with longer spans than individuals but always peopled by those shorter-lived humans, have difficulty learning from previous generations. Somewhere in his book, Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, the insatiably curious physicist wrote that we live our lives, see where we’ve gone wrong, and then die. For some reason, the simple truth of that statement, the flat-footed way he phrased it, amuses me no end. That's us, all right! And is that how it will be with our species as a whole? I wonder. They came into existence, succeeded magnificently for a while, then messed it up and went extinct. Maybe. Understanding too late--.

Besides understanding, however, there’s no denying the strong element of escape in much of my reading, and often these hungers pull in decidedly opposite directions. When the world is too much with me and I want to drown out the clamor of politicians who have once again invaded my thoughts with one outrageous act or speech after another, my hunger for escape pulls away from my hunger for understanding, and I can only feed them in turn, first one and then the other, these jealous rivals, setting aside Jimmy Carter’s Keeping Faith for The Moffats, by Eleanor Estes.

|

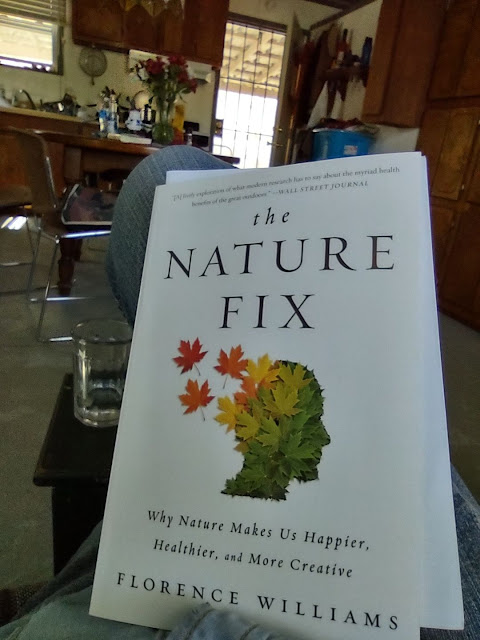

| Looking for understanding, |

|

| the search continues. |

Caveat emptor: I’ll stop here for a moment to remind myself and my readers that naming desires, like naming emotions, distorts our inner reality. They are not things and do not occur singly, and my attempts to tease out separate strands from an inchoate stream can be only a partial and misleading picture. All analysis distorts. Keep that in mind, please, and what I write here will not seem, perhaps, quite so absurd!

|

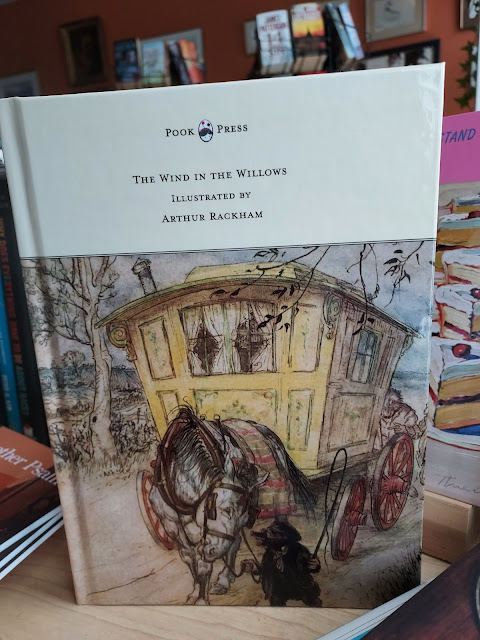

| The open road! Escape! |

And now I’m thinking that understanding and escape are very earthbound dimensions of reading hunger, very, very human, and that there is something else, woven tightly into these hungers and yet also very different, and that is our longing to live beyond the limits of our individual life spans, not only longer but also larger. You see instantly how the desire to expand beyond cannot be separated from hunger for understanding or for escape—and yet, do you also see that it cannot be completely expressed by those two hungers?

I have more to say about the comfort of remembering, which also lets us slip time's constraints.

Through the Looking Glass brings back, for me, the excitement I felt when I ran into the kitchen to tell my mother, “It’s a chessboard!” Lewis Carroll had not stated it so baldly, and my parents had not explained the story to me that way, but all of a sudden, reading it to myself, I had seen the chessboard when the Knight told Alice he could go no farther because he had reached the end of his move, and I had to run and tell my mother, who responded, “You didn’t know that?” No, I didn’t, but the excitement of my discovery was not dampened by her amusement, because I discovered it for myself, as I still remember with pleasure.

If I were to pick up right now, today, Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, it would carry me back to the Parc Monceau in Paris (as merely thinking of the book carries me back), especially if I had the French paperback. One summer, day after day I went to the Parc Monceau with that book in hand, L’insoutenable légèreté de l’ être, lost in an Eastern European world inside the landscaped French world around me in my dream city far from home.

And Wind in the Willows! I read that book to my son, giving the different animal characters different voices, and we had a wonderful time, which he still remembers. Then when the Artist and I had a layover in the Detroit airport on our way home from France, we read to each other (from a battered paperback copy that is here in my house somewhere, but where?) the chapter “Dolce Domum,” tears streaming down our faces, while all around us business people busily consulted their Blackberries and the contents of their briefcases.

Are you still with me? Are you as tired as Sunny Juliet of my egghead ruminations? “Momma, get real!”

|

| Real is snow in thick flurries and wind that drifts it across roads! |

Well, here’s what was real for me on Monday evening as the blizzard swirled and on Tuesday morning when darkness had not as yet retreated: I was reading, for the first time in years, Jim Harrison’s novel, Dalva. First published in 1988, Dalva is written in the first person, the first and third sections in a woman’s voice, and what inspired me to revisit this book in 2025 was the new collection of Jim’s work in French translation that concentrates on his women characters, both in first-person stories and in third-person works with central female characters.

I have to admit that when Dalva first came out, it was hard for me to “hear” the female narrator’s voice, what with Jim’s own gravelly, very masculine speaking voice so familiar to my ear. Reading the book now is a very different experience. For one thing, Jim’s speaking voice has been gone for nine years, and he had been gone from Michigan longer than that, gone to live in Montana and Arizona. But also I am 37 years older than when I first read this novel. Thirty-seven years of varied life experience, shall we say, gives me a much richer perspective, and now Dalva’s voice comes through strong and clear to me, and I am loving this book, truly loving it, and have a much deeper appreciation for what the author accomplished, not only in writing from a woman’s point of view but in speaking so many truths.

It is somewhat a mystery to me how the rich can feel so utterly fatigued and victimized.

...

Now there’s a specific banality to rage as a reaction, an unearned sense of cleansing virtue.

...

The tomatoes looked as if they were suffocating in the glass jars, livid red and suffering.

...

…I had told him that I was without a specific talent, other than that of curiosity, and he saw that as a large item. It is terrible to assume life is one thing, only to discover it is another. A highly mobile curiosity gives you the option of looking into alternatives.

There is also, I must admit (Another admission? Is this post becoming overly confessional?) my love for southeast Arizona (a love that took me by surprise), and the way the mountains and high desert haunt my northern Michigan winter finds solace in Harrison’s descriptions of places not far from my former winter stomping grounds in Cochise County. He was just a couple of mountain ranges west and south. Hackberry trees along dry streambeds, mesquite on overgrazed acreage, eroded gulches, alligator juniper at higher elevations—all that. I came to know such country intimately.

How much poorer my present life would be had I not come back to re-read this novel! How many hungers it satisfies!

I would defend my answer to my own original question by noting that I spend no time whatsoever watching television and none drinking in bars, although as a word-addicted, dream-addled, introverted widow I do not hold my priorities up as superior to anyone else’s. All I’m saying is that reading is a priority in my life, and this is where I look for comfort and strength and beauty and understanding.

Also, never fear, Sunny and I manage a lot of dog-and-mom time, indoors and out!