David and I decided to make an expedition to Inverness, up in inland Citrus County, on the Friday before Presidents Day Monday. If two-lane state roads are “blue highways” (in William Least Heat Moon’s memorable terminology), the even narrower two-lane county highways of Florida might be called “indigo roads.” We knew it would be warm in the car, so after Sarah had a good indoor play session with Weiser and Ida, we let her stay home for a day.

Backtracking west to Pine Island for coffee at Willy’s Tropical Breeze Café before entering the highway, we had coffee at a picnic table on the deck, where I filled the first page in my sketchbook for three years. Sketching is something I do only in Florida and it’s nothing I plan to use in any way, but it felt good to break through the impasse at last. David is a very encouraging and unobtrusive teacher. That day he gave me helpful tips on perspective and shading. It was a good way to start the dy.

Then it was north on 19 and east on an indigo road I chose from the gazetteer, only because it went in the direction we wanted to go, with no idea what kind of road we would encounter—even whether or not it would be paved. It could not have been better! Paved, smooth, rural, and lined with horse farms and cattle ranches!

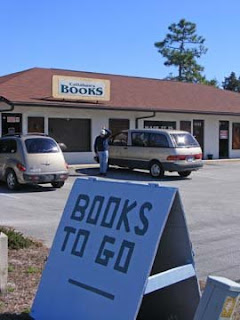

We might have driven more slowly and stopped along the way, except that we knew that the bookstore in Inverness, Rainy Day Editions, closed at 2 p.m., and this time we were determined to make it in the door. Made it! I asked proprietor Bill Bissell about the arm he’d broken three years ago, and he was touched that we remembered. He has had his bookstore in Inverness for 17 years, and before that he worked in a bookstore in St. Petersburg. When I asked if he would pose for a picture with me, he exclaimed, “I love this business!” Me, too! I love these encounters with far-flung colleagues, I was happy with the books I found to buy from Bill, and he was pleased, too, with my selections.

Well, usually in Inverness we go to the Deco Café, across from the courthouse, but this time something drew us to a new place, the Olde Towne Latin Café, even though there was no one sitting at either outdoor table, and inside we found the small place lively and cheery, with two other tables occupied and a customer at the counter, as well. We shared a big, hot, pressed Cuban sandwich, and I had the Cuban coffee. Both were perfect.

Now if only I could be sure that he read Christopher Milne’s

The Path Through the Woods, which David and I are reading now with great delight, before selling it to me! It’s not a member of the “books on books” category but also of the even smaller category of “books on bookselling.” But I did not skip the first half of the book, covering Milne’s university days as a mathematics student and his five years as a WWII sapper. He is such an engaging writer, with such love for the world in all its detail and ambiguity, that every page is a joy.

Completely satisfied with the visit to Inverness, west out of town on 44 we went, then south from Lecanto until we’d closed the loop begun earlier in the day, more than ready to rejoin Sarah in quiet little Aripeka.

And now, about some of the books I’ve read recently….

BOOKS ABOUT DOGS:

Linda Colflesh, in

Making Friends: Training Your Dog Positively, offers reassuring words to any dog owner whose pet is inclined to jump up on visitors. Sarah never jumps on us, but we have to be vigilant to keep her from overwhelming friends and visitors to the bookstore and gallery, and it isn’t helpful in those situations for someone to say, “Oh, it’s all right!” No, it isn’t! It’s not all right with us! Here’s how Colflesh begins that section:

Jumping up is the behavior problem listed most frequently on the registration sheets for my obedience classes. It is a good behavior problem to have, because it means you have a normal, friendly dog. I’d be concerned about the temperament of a dog, especially a puppy, who didn’t want to jump up.

See what I mean about encouraging? She admits it’s a problem but tells you it’s a “good … problem to have” and goes on to compliment your dog in the same sentence. Her cure for jumping up is not some kind of punishment, either, much less separating your dog from company (which doesn’t give the dog a chance to learn anything), but teaching the dog how to greet people—sitting to be petted. The attention the dog gets for doing the right thing is the reward. This example illustrates Colflesh’s general dog training philosophy.

Essential Dog, by Caroline Davis, is a Reader’s Digest book, very well organized, thoroughly illustrated, and clearly written. The main chapter headings are “Choosing a Dog,” “Canine Behavior,” Caring for a Dog,” “Training Your Dog,” and “Health Care.” Certain tips and bits of specific information are set in boxes, giving each page an easy-to-read magazine look. This would be one good source book for a family thinking about getting a dog. A table listing pros and cons of purebred vs. crossbred vs. mongrel is pretty even-handed, too, I’m glad to report.

Such fairness is not always present in advice on choosing a dog, authors Brian Kilcommons & Michael Capuzzo write in

Mutts, America’s Dogs: A Guide to Choosing, Loving, and Living With Our Most Popular Canine. Instead, many books begin to answer the question of choosing a dog with a lengthy discussion of the different purebred types, warning against shelter dogs and those of unknown origin.

Added to this colossal waste is the spiritual cost of killing man’s best friend. The periodic slaughter of wolves, dolphins, or other wild creatures brings international outcry and is said to diminish our humanity; the annual slaughter of millions of equally intelligent dogs is routinely accepted….

“Every day in this country, parents with young children confront a choice—what kind of dog for our family?—armed with misleading or all the wrong information. Too often, they pass on these worthy but doomed dogs in favor of a purebred.

Full Disclosure (in case anyone doesn’t already know this): Our last dog (Nikki) was “pure mutt,” our present dog (Sarah) a “mixed breed.” So it won’t surprise anyone who knows me when I say that I learned a lot from Linda Colflesh and found the Caroline Davis book very informative, but it was

Mutts that won my heart. Early on I was laughing out loud at the authors’ listing of the “ten most popular dogs in America.” (Almost 60 percent of American dogs are mutts, they claim, so it is wrong to call any purebred the top dog in America.) Their irresistible list—and if you’ve ever visited an animal shelter, you’ve seen all these dogs—begins with the Brown Dog! The main part of the book is then divided into Sporting Mutts, Hound Mutts, Working Mutts, etc. (and yes, under Herding Mutts, they say that the Border Collie-Australian Shepherd Mix owner should “expect a ton too much dog for average household use”), with portraits and stories of real individual mutts in each category. Turning the pages, looking at the pictures, and reading the stories is like looking at an album of every neighborhood dog you ever knew. Well, at least that would be true of the neighborhood where I grew up, and it’s certainly true of our winter neighborhood here in Aripeka.

BOOKS ABOUT PLACES AND LIVES:

I bought

The Stones of Balazuc, by John Merriman, because it is the story of a town in France’s Ardèche province, a region we visited almost eight years ago, stopping overnight at the home of an artist friend from Traverse City. Traveling without itinerary, in our usual make-no-reservations style, we were pleased to find Jeanie’s little village and stopped at a small grocery store, certain that everyone in town would be familiar with the woman painter from America. No, they didn’t recall any American women, artists or otherwise. I played what I expected to be my trump card: her house is an old silkworm farm. (Surely that would identify the place!) “Oh, well, most of the old houses around here were silkworm farms,” the shopkeeper said with a shrug.

Really!There was a happy ending to this story, when I asked for a phone book and found Jeanie and the shopkeeper, after answering my question about the pay phone outside (yes, you needed a card to use it, and no, the shop didn’t sell the cards), offered me the use of her cell phone. (It kills me when people tell me that the French don’t like Americans! They were nothing but nice to us, everywhere we went, and David doesn’t even speak French.) Jeanie answered, and everything worked out.

Long digression.

Je m’excuse! What I started to say is that the book interested me because it’s set in a region of France with which we have some slight personal familiarity. So David was keen, too, and I started reading it aloud, and we found it engaging despite the academic style (and frequent sentences that editing could have improved), but what we really wanted was something about the old silkworm days, to give us a background on the place where we had spent such a memorable night. Ah, marvelous! That, it turns out, is really the meat and potatoes of the book—or should I say, in the spirit of the province, the wine and chestnuts?

Mais, oh-là-là, les pauvres Ardèchois! One hundred, two hundred years ago, Balazuc was facing challenges similar to those faced today by Northport, Michigan, and other small American towns: that is, the entire province of Ardèche, like other regions, was losing its young people in an unprecedented rural exodus known as

le grand départ. Much of the reason for the exodus from the Ardèche was a tale frequently occurring in the history of agricultural the world over, that of a land given over to monoculture, unable to support itself when the single crop failed. (Does Ireland come to mind?)

Actually, it was even worse than that for Balazuc. The earth there still more rock than soil, Balazuc’s peasants and small land-holders did not completely forsake cultivation of grapes or chestnut trees for mulberry trees and silkworms, but following on the heels of the parasite that devastated the silkworms came plant lice in the vineyards and chestnut blight. Nor was that all. Year after year of massive floods carried away the little soil that had scraped together to produce a few potatoes. Chapter Four closes plaintively: “Abandoned terraces on steep slopes today offer silent witness to

le grand départ.”

That was as far as we got before the story bogged down, and we enjoyed that much. he fault of the writing is not the author’s academic style so much as the way he orders sentences within paragraphs. Logic is lacking, and the confusion of being hopped back and forth with so little ceremony is discouraging. Too bad, because the research in the book is first-rate and the facts themselves fascinating.

On my own, I recently finished

Toute une vie pour se déniaiser, by Amelie Plume. This interior dialogue between two facets of one woman’s personality, a woman exactly my own age, reviewing her life from childhood to grandmotherhood, could not fail to hold my attention. After all, although the author (and the two internal voices that make up her plural “I”) has spent her sixty years in Switzerland, the Sixties in Europe and the Sixties in America were remarkably similar. Her desire to capture the present moment as it passes rang a sympathetic tone in me, too.

La vie qui vit, le temps qui s’écoule—oui, oui! Mysterious moments occurred, when context left opaque for me the author’s neologisms (or

Suissismes?). Never mind. Sometimes it feels best to read without a dictionary, to be immersed in the author’s language and swim as best one can. In the same way, I always think that people who find poetry difficult should just let it rain down on them rather than trying to analyze every line to death in a laborious attempt to “understand.”

My next choice was Anne Tyler’s

Digging to America, and when I bought it, the woman at the register said her book club had read it. “Was it good?” I asked, making conversation. She hesitated before replying in a noncommittal tone, “It was different.” “I like Anne Tyler,” I offered, hoping to get her to say more. “Yes,” the woman said calmly, “she’s thought-provoking.” Not the first description that would come to my mind, but not one I could reject as false, either. What I appreciate about other Tyler novels I’ve read is the gentle eccentricity of her characters. They are never maniacs but can usually be described as “oddballs,” people who don’t quite fit into the American mainstream but drift and eddy about in their own quiet backwaters. Digging to America is different. Its theme might be “outsiderness” (a term that only appears once, very late in the novel), but it is the outsiderness of temperament and culture, not of eccentricity.

The characters in

Digging to America, most of them very much in the mainstream of Baltimore’s educated middle class, feel themselves to be different. Sixty-year-old Maryam, a widow and new grandmother of a baby adopted from Korea, feels different because she was born and grew up in Iran. Hers was also, to all appearances, an old-fashioned arranged marriage, though we learn from her reflections on that marriage that there was much more to the story than her son realizes. That son, Sami, whom his mother sees as thoroughly American, though he grew up in the United States speaking American English, says he always felt he had to try harder to “fit in” than his Anglo-appearing friends. As an adult, to entertain Iranian-American relatives, he likes to rant about “Americans” as if he were not one himself. (I’ve heard fourth-generation Americans do the same thing. It seems a very American thing to do. Do people in all cultures do this?) Ziba, his wife, born in Iran but educated in the U.S., feels she and her husband are different even from their Iranian relatives. After all, they could not have a biological child of their own, and their Korean-born daughter does not carry their bloodline.

The other couple whose adopted Korean baby arrived on the same plane—and with whom Sami and Ziba have bonded over the years, thanks to the other woman’s insistence that the two girls grow up as friends--have no ethnic issues with their own American-ness, and the Iranian-Americans cannot imagine that organic, know-it-all Bitsy and laid-back, easy-going Brad would feel any insecurity at all about who they are. But Bitsy doesn’t want anyone to know that Brad is her second husband, and having given up her own career plans for her second marriage, she does everything to insure that motherhood will take up every moment of her day (by keeping her baby in cloth diapers, not enrolling her in preschool, etc.) and still secretly worries about how little she has done with her life.

One element of suspense in this story (Tyler stories all contain elements of mild suspense, though no reader will be on the edge of her seat with concern) has to do with Ziba’s mother-in-law, Maryah, and Bitsy’s father, Dave. After Bitsy’s mother, Connie, dies, will Dave and Maryah become a couple? If not, will the failure be traceable to cultural and ethnic differences? “You belong as much as I do,” Dave tells Maryah earnestly. We

all think the others belong more.” Just the way we think other families celebrate a “real” Christmas or (this came to my mind) we think there were kids in high school so popular or gifted that they didn’t worry about being liked or being successful.

The two young couples annually celebrate the “Arrival” of their adopted daughters with a party that grows larger year by year. Sami and Ziba have called their Korean baby Susan, while Brad and Bitsy kept Ho-Jin’s given birth name and do the same with their second adopted child, Xiu-Mei from China. How do the children feel about growing up American? Do they feel different from native-born children living with birth parents? And how will the two adoptive families by changed by having these children in their midst? The ending is surprising, not at all telegraphed ahead of time, but it’s quietly perfect. Has no one yet conceived of a film version of

Digging to America? I still don’t have a clue what reservations the woman in the book club had with this book!

David is reading and generally absorbing books about painting, along with Joyce Cary’s novel about a painter,

The Horse’s Mouth, Cormac McCarthy’s

The Road, and

Bring on the Empty Horses, by David Niven.