|

| Sunny and I get out every morning, and the desert is greening up now. |

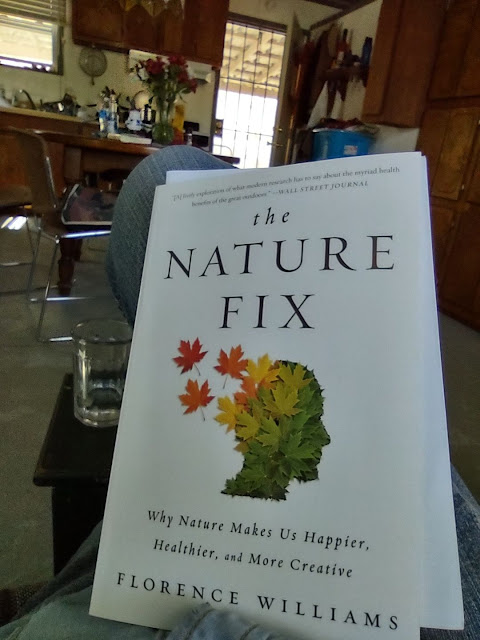

Strange beings, human beings, aren’t we? So often we forget that we are not separate from nature but natural creatures ourselves, which means that we are always “in,” as in “part of” nature. At the same time, we also know the difference between indoors and outdoors, the difference between houses and shopping malls and office buildings and classrooms as opposed to parks and woods, beaches, mountains, and campgrounds, and so, in a way, the scientific “news” in Florence Williams’s book, The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative (NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 2017, paper, $15.95) didn’t seem like news to me at all.

|

| Reading indoors, but with doors and windows open, birdsong audible in the background |

When I worked office jobs, back in the 1970s and 1980s, I often felt like a captive, so tethered to my telephone and typewriter (these were the old days) for hours, on such a short leash, that even going down the hall to the restroom meant being jerked back by a ringing phone. But was that just me -- or me and people like me but not everyone? What about those who say, “I’m not an outdoor person”?

Ah, but that’s where it gets interesting! Because some of the researchers looking at all the ways the outdoors benefits us felt no personal desire themselves to leave their computers and laboratories and were skeptical of other researchers’ work that found huge gains in physical and mental health among test populations. Some even work on developing “virtual nature,” an oxymoron if I ever heard one but quite a lively field, apparently. (Go figure!)

One such skeptic was Frances Kuo, director of the Landscape and Human Health Laboratory at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, whose research focused on urban environments, comparing public housing apartment complexes with various sorts of courtyards: (1) those with no greenery whatsoever, (2) those with both greenery and concrete, and (3) those with grass and trees. Over a two-year period, her study found the buildings in the middle group had 42% fewer crimes compared to the concrete-only group, and the buildings with the greenest surroundings had, compared to the non-green courtyard buildings, 48% fewer property crimes and 56% fewer violent crimes.

“I am not historically a nature lover,” Kuo told me. “I had no personal intuition when I started that these findings would come out the way they have. But twenty years later, I have convinced myself.”

So to the question, “Do we really need to study this to know that nature is necessary to human beings?” the answer is yes, because in modern Western civilization Western science is such a driving force in our lives that until scientists are convinced, natural needs can be and usually are downplayed or outright ignored.

The Finns got into the research game early, for economic reasons, wanting to lower health care costs. Their studies would also, they believed, provide data for city planners, depending on conclusions those studies might reach, and for them subjects do more than take a walk in the park. Data is key. Questionnaires, blood pressure samples, heart rate measurements, even saliva samples taken before and after a half-hour walk, for example. The bottom line for the Finns was that five hours a month in natural settings was the minimum for the biggest health gains.

And then there was Roger Ulrich, not a skeptic but simply a curious scientist.

A young psychologist named Roger Ulrich was curious why so many Michigan drivers chose to go out of their way to take a tree-lined roadway to the mall.

So first he had a group of volunteers in the 1980s view slides of nature scenes, while the another group saw “utilitarian urban buildings.” Okay, good. Next he subjected volunteers first to stress, by showing them “bloody accidents in a woodworking shop” (No, thank you!), and then showed them either scenes of either nature or city to see how long it would take them to recover from the stress. EEG readings of what Williams calls the “brains-on-nature” viewers returned to baseline within five minutes, while the urban viewers continued to exhibit stress ten minutes later.

These studies, Williams tells us, were considered “soft science” at the time, and the field did not really grow for decades, but Ulrich kept at it. He followed the records of hospital patients following gallbladder surgery, those whose rooms had a window view of trees and those who could see only a brick wall from their beds.

He found that the patients with the green views needed fewer postoperative days in the hospital, requested less pain medication and were described in nurses’ notes as having better attitudes. Published in Science in 1984, the study made a splash and has been cited by thousands of researchers. If you’ve ever noticed a nature photograph on the ceiling or walls of your dentist’s exam room, you have Ulrich to thank.

Another name that appears over and over in The Nature Fix is that of data-seeker David Strayer. He’s the cognitive psychology researcher from the University of Utah who discovered what has been called (one of his friends coined the term) the “3-day effect” (explained in the Williams book without the popular term being used), a key to which is being in the wilderness unplugged – no cell phone, smart watch, or anything like that. Because the clever adaptations we make in our artificial environments are often not consistent with the way our brains work, our brains need restoration from time to time.

I mean, can you believe that 36% of people [Americans only?] check their cell phones during sex?! No citation appears for this claim, made by one of Strayer’s academic wilderness companion researchers. Strayer himself made the statement that the “average person looks at their phone 150 times a day,” which I can quite easily believe.

Science, then, has found the following gains from time outdoors “in nature”: less stress, lowered anxiety, lowered aggression, heightened optimism, increased sense of well-being, and increased feelings of connection not only to “nature” but also to other human beings.

(Obviously all this has surprised a lot of people. Do they forget how and where our species evolved? We are, first and foremost, earthlings! Yet I notice that the big money man behind the world’s arguably most experimental car, who is eager to send human beings to Mars, has yet to put himself into orbit. He sent a car instead. And then, see The Starship and the Canoe, by Kenneth Brower, a book I highly recommend, about physicist Freeman Dyson and his son, George Dyson. The physicist, obsessed with space travel, was for a time a regular reviewer for the New York Review of Books, a highly respected academic, but his son, living in a treehouse, was seen as an eccentric dreamer. As to which man can claim a firmer grasp of the human condition, its strengths and its limitations, you can pretty much guess where I come down -- not that I expect everyone to agree with me….)

Here's what some other countries are doing to meet their citizens' need for time in nature:

➡️ Sweden recognizes “horticulture therapy.”

➡️ Singapore, the third-densest country on earth, intentionally increased its percentage of green space from 36% to 47%, even as its population grew by over two million people.

➡️ Japan has a long cultural history of attention to nature, and the country has developed 48 official “Forest Therapy” trails. Japanese medicine also recognizes “forest medicine” as a specialty.

Can it be that we human beings are finally waking up and paying attention to what we are and where we live? (Earthlings, earth.)

Recommendations From the Author

Williams draws her recommendations from various scientific sources, and one she particularly likes is the “nature pyramid” concept promoted by Tom Beatley of the Biophilic Cities Project at the University of Virginia. (Remember the food pyramid, you old folks?) The base of the nature pyramid is “daily interactions with nearby nature that help us destress, find focus and lighten our mental fatigue." (When I was working those office jobs, at least I walked an hour to work through my neighborhood and a campus with plenty of greenery and past a couple of ponds.) The next level up is weekly outings, followed by monthly excursions – each level also being more immersive – and finally reaching, at the summit, “rare but essential doses of wilderness.” Like this --

|

| Yes, I made this pyramid just for YOU! |

If you live in the country or in an urban environment with plenty of parks, you are lucky. (Stepkids and grandkids take note: Top city on the “ParkScore” index is Minneapolis.) Yet for myself, for all the time I spend outdoors, both in the Arizona winter and my Michigan summer, I have to admit I rarely if ever reach the pinnacle, retreating for at least three days into wilderness. Do you think exceeding the minimum on the other levels can make up for not reaching the top? That's something for scientists to check out, don't you think?

|

| Desert thorn in bloom, Cochise County, AZ |

Here I am (below) with my new "cousins" from the Phoenix area. When they came to visit, we hiked part of the Echo Canyon Loop in the Chiricahua National Monument. We loved our outdoor time together!

|

| Me with Jim |

|

| Carol and me |

Where can you walk in other countries?

Hold onto your heartstrings! The answers are interesting. Finland has the concept of “everyman’s right,” which means there is no such thing as “trespassing” in privately owned forests. Anyone can walk and pick berries and mushrooms. The only forbidden activities on private land are cutting timber and hunting game. Scotland has similar “right-to-roam” laws. There you are prohibited from hunting, sheep-stealing, and digging up plants, but you can roam to your heart’s desire.

|

| America: Land of the Free? |

One minor criticism

This book could really have used an index! But imperfection is – well, an opportunity to embrace wabi sabi, right? The Artist loved that whole idea, and it's pretty much the way we two imperfect beings lived together….

|

| Dear imperfection of a perfectly shaped clay pot! |

2 comments:

Great review of this book, Pamela! I love my adventures outdoors with my camera. They are truly in synch with what the book says about getting a nature fix. I found the information about having no "no trespassing" laws in some countries interesting. I sure could have used that on several of my photo-ops. I have found, however, that when I've asked owners if I could go on their land to take pictures, they've been fine with it.

Karen, your comment about property owners reminds me that when I stopped one spring to photograph the Neilsons' apricot tree and surrounding cherry orchard, Norm came over and invited me to take the farm road through his place to the back orchard! Lovely people and wonderful Leelanau Township neighbors!

Post a Comment