|

| On last Wednesday morning's walk |

Up

early in the dark on Sunday morning, habit too strong to let me “sleep in,” I

read through the last few chapters of the first half of Pride and Prejudice, making notes for the discussion

I am to lead on Tuesday night, and then picked up a book I haven’t had time to

open in the last two busy weeks, Farmacology: What Innovative Family Farming

Can Teach Us About Health and Healing (NY: William Morrow, 2013), by Daphne Miller, M.D. A

review in Acres USA brought this book to my attention, and it sounded like a must-have

for my bookstore’s section of new titles in agriculture and gardening, so I

ordered two copies a few weeks back. Now I feel the same way I did the first

few weeks of my freshman year in college, learning huge amounts at a tremendous

speed and seeing connections everywhere. But let me begin at the beginning of

Sunday morning.

Wow! I had trusted the book would be

interesting but hadn’t expected to meet my old friend (no, we’ve never met; I

only know his work) Wendell Berry on the very first page. Only a few pages

further in – by page 8, to be precise -- my head was humming like a basswood

tree full of honeybees, when the author, through a chance encounter with a

little book called The Soul of Soil, recounts how she began wondering if principles for

rejuvenating soil could be applied to human health. When a presenting medical

problem is simple, she writes, the focus of the physician can be narrow and

simple, as well. “But most of the time our health needs are more complex and dynamic”

--. I stop in my tracks mid-sentence, my own mind italicizing the words

“complex and dynamic.” Associations to into high gear, branching out in surprising directions, and I have to put

the book down to give myself time to catch up and slow down again.

This

fall I’m taking a non-credit class in beginning drawing, the first art class

I’ve ever taken in my life, and in our second session the instructor gave us

exercises to do to move us from our left to right brains: “The left brain does

not like complexity,” she told us, so when we embark on a complex drawing

without recognizable, nameable parts, by attempting to copy a line drawing

while looking at it only upside-down, the left brain “will give up and get out

of the way.” When the left brain “gets out of the way,” we can no longer rely

on pulling stored symbols out of memory but must concentrate on shapes, lines,

and relationships, actually seeing rather than thinking about what’s in front of us. (And yes, the

instructor, Elizabeth Abeel, does draw heavily from the Betty Edwards book, Drawing

on the Right Side of the Brain.)

You see

the connection? Miller writes that most of our health needs are “complex and

dynamic,” and I hear my drawing instructor saying, “The left brain does not

like complexity,” and I see monoculture and pesticides, along with restricted

diets, antibacterial cleaners, prescription drugs and supplements as left-brain

“solutions,” spawning in their wake myriad new problems because they fail to

address the real-world complexity. Miller’s mention on the same page of

“reductionist medical training,” the conceptual division of the body into parts

for focused study and diagnosis, brought to my mind Bergson’s

intellect/intuition distinction, the intellect being our problem-solving,

“engineer’s” brain, conceptually breaking reality into parts and often gaining

a practical advantage by doing so but making a mistake by believing the

analysis has uncovered a deeper reality. The tools created by analysis (i.e.,

reductionist thinking), Bergson insisted, must always misrepresent reality in order to make its

manipulation possible.

Miller contrasts reductionist with holistic, Abeel and Edwards draw the line between left and right brain, and Bergson distinguishes intellect from intuition. I'm only on page 8 of Miller's book, and my head is already reeling, as Wendell Berry and Henri Bergson and

drawing and seeing and soil and farming show themselves as always-already

aspects of one great whole.

I

need to pause here and make it clear that neither Bergson nor Miller would have

us do away with intellect or analysis. We need intellect and its work.

We must always remember, however, that “the map is not the territory," and that there

will always be more to reality than the most minutely painstaking analysis can show.

Back to

the rest of Miller’s show-stopper sentence, but let me begin again at its

beginning:

But most of the time our health needs are more complex and dynamic, just like the soil, and most of what ails us today – depression, anxiety, diabetes, heart disease, fatigue – is multifactorial, chronic, and not well served by a static and highly focused approach.

“Static”

is what analysis gives us. Snapshots. But life is never static, as Bergson insisted over

100 years ago. We are not machines. We are not laboratory creations but living beings – as

Wendell Berry reminds us over and over, creatures of the soil.

I

want everyone

I know to read

this book – farmers, medical workers, office workers, parents of young children

and older, retired people. “Can’t afford” fresh local produce? I saw a great

bumper sticker not long ago: “You can either pay the farmer or pay the doctor.”

This is

what happens when one lives surrounded by books. What did Christopher Morley’s

old bookseller character say about books being more explosive than dynamite, by

virtue of the ideas in them?

Meanwhile,

the list of recent topics I have yet to cover here in “Books in Northport”

grows ever longer: “Leelanau UnCaged,” visiting poets (Fleda Brown, Arturo

Mantecón, and Mark Statman), and soil erosion are the three on the top of

the list, unless, that is -- exciting as those topics are -- they get bumped down

the line by yet another glorious streaking comet of written excitement that I can’t

wait to share. Would it be possible to combine topics and do a post on “Poetry

and Soil Erosion”? Possible, surely, but the result would probably too long to

hold readers to the end....

|

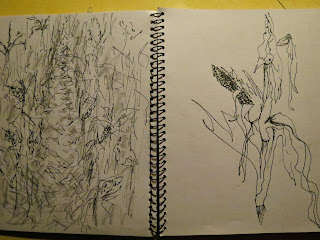

| Field corn drawings from 2012 stillness project |

Well, what is

happening in the countryside these days? Farmers who got in their field

corn before the last few several days of drenching rain are undoubtedly happy. It’s bow

season for deer; how is that working out in the rain? Visitors come Up North for fall color have surely been

gratified by its beginning, despite the wet weather, and weather remains warm,

so even annual flowers are still bright and lively.

Ever in

motion, ever complex, ever fascinating, the world brings us every day new joys

and challenges, painful shocks and delightful surprises. Drawing and writing,

we create a record of time that will never, in today’s specificity, return.

2 comments:

Pamela,

This is an interesting commentary. Reading it prompted me to search out a quote from In Defense Of Food by Michael Pollan. To paraphrase Pollan, At every level, from the soil to the plate, the industrialization of the food chain has involved a process of chemical and biological simplification. It starts with industrial fertilizers, which grossly simplify the biochemistry of the soil.... These soil treatments completely overlook the importance of biological activity in the soil and the contribution to plant health of the complex underground ecosystem of soil microbes, earthworms, and mycorrhizal fungi. Harsh chemical fertilizers and pesticides depress or destroy this biological activity. Plants can live on this fast-food diet of chemicals but it leaves them more vulnerable to pests and diseases and appears to diminish their nutritional quality.

Another reason to purchase local, organic foods, huh?

On another matter, is the P&P discussion Tuesday or Wednesday?

Marilyn, thank you for bringing in the very pertinent quote from Michael Pollan. I wondered at first which Marilyn you were, then saw your question about P&P. We're on for Tuesday at Big Steve's house, as Wednesday is my drawing class in TC. Hasta banana!

Post a Comment