[In China] I took deep interest … in the farming problems of our neighbors, the difficulties of raising crops…. I watched the turn of seasons and was anxious with the farmers when there was no rain and yearned with them in their prayer processions and was grateful when sometimes the rain did fall.

- Pearl S. Buck, My Several Worlds: A Personal Record

Up North, when days finally grow long and bright again, the question asked between people meeting for the first time in this new year is always the same: “How was your winter?”

My answer this year: “In retrospect, it went fast.”

I admit that individual days sometimes felt long, and yet, each week, as I looked back on it, seemed to have flown by. Spring’s arrival, however, seemed reluctant as back and forth it went, a yo-yo season, giving us hope only to dash our optimism the following day. Yet difficult as were those days of March and April, they were cold spring days, January now only a memory.

Cherry blossom was unspectacular this year in my immediate neighborhood. We had ice and rain and wind, and though trees bloomed, I missed the usual rolling acres of brilliantly white flowering trees in the spring sun. Either I missed it, or the wind and rain tore the blossoms untimely from the boughs. If I'm correct about there having been a shorter flowering time, will it affect the harvest? Farmers need a lot of faith to keep going, it seems.

|

| Annuals to add POP to perennial borders |

One of the garden centers where I buy flowering annuals changed hands this past year, and when I asked one of the new owners how things were going he remarked—this was last Sunday morning—that people were biding their time, reluctant to plant with the weather as cool as it still was. I had risked bean seeds, and they came up, but then a chilly morning nipped part of a row. I filled in the row with new seeds. Does that take faith? I don’t know that I'm brimming with faith, but I plant and hope for the best and am delighted (by what seems a miracle!) when seedlings emerge from the soil.

Now—suddenly, it seems!—it is June, and there are no more slow days. Between sunrise and sunset we have more than 15 hours, so the days are long, but each one speeds by. As illustration and evidence, I offer below images of trees leafing out in late May. First, a roadside woods at that all-too-brief impressionist stage, the spring day when I always long for a ‘pause’ button so as to drink my greedy fill of this delicate, tender, fleeting time that is gone too soon. Then, our Leelanau woods only two days later. The first green of spring: Now you see it, now you don’t!

|

| One spring day -- |

|

| Two days later -- |

|

| And THEN! It's a jungle! |

My personal and business life take on the speed of the season, which is why my recent trip to Kalamazoo was only an overnight turnaround. I could stay there for a month and still not have enough time with family and friends, but too much awaits my attention at home, so home I came the next day to tend to it all: planning for bookstore events with book orders and publicity, and planning for summer visitors to my home (and for my own stolen moments of leisure) by getting yard and gardens in shape for the season. Marilyn Zimmerman's book launch is next week!!!

|

| Mark your calendar for June 10, Dog Ears Books, 5-7 p.m.! |

In the midst of all this, the disappearance of my billfold, holding driver’s license and credit cards, was a minor crisis. Did I leave it somewhere? Drop it somewhere? Was it in the house “in plain sight” and I just couldn’t see it? Over and over I mentally retraced my steps ... called places I’d been on Friday and Saturday ... looked and looked and looked ... through every bag, under car seats, at home and in my shop. It is so maddeningly tedious, having to give over mental energy to such a boring, repetitive task, don’t you find?

But on Monday morning my car had to go in for a brake job in Leland, and since I could make no progress on the search while the car was in the garage, I put the whole problem on the back burner, walking from Van's garage down Main Street to Trish’s Dishes to get a coffee to go, encountering a couple of friends along the way, and then making my leisurely way back to the river to find a perch on the dock of a shanty belonging to friends there in Fishtown. I'd texted Charlie that I would be there but hadn't had a reply, so I just made myself at home, as the Artist did so many times over the years.

|

| Looking lake ward |

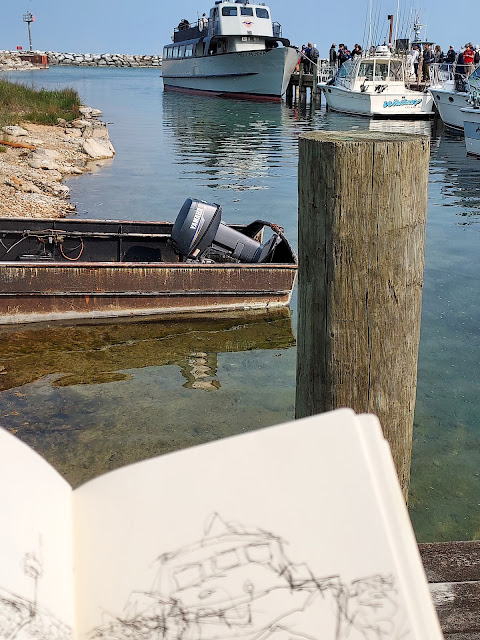

A glorious morning! The sun was shining, and the breeze was alive with that wonderfully familiar, fresh-fishy aroma of the river. Men were at work on the dock opposite, where a few early morning tourists strolled. Passengers gathered to board the Mishe-Mokwa for a day trip to South Manitou Island. Gulls flew overhead, and song sparrows sang. Now and then a duck paddled about near the pilings.

It was very near here, just south of the river mouth, that the Artist spent a night on the beach long ago and wandered into town the next morning to the Bluebird, where Grandma Telgard said immediately to a member of her kitchen staff, “This boy needs a cup of coffee!” That was years before we met, but in later years together we spent many, many hours in, around, and near Fishtown, only a pleasant walk from our old Leland home.

Back to the present. Now, in 2025, for weeks and weeks I have been carrying my sketchbook with me everywhere I’ve gone, along with a set of drawing pens sent to me by a friend for my birthday. The last serious sketches made in the book were from 2015. A whole decade ago! How is that possible? Finally, there on the dock, I took out sketchbook and pens and applied myself to the scene. The results were laughable, but results didn’t matter. I was there and nowhere else, practicing drawing as meditation. Perfectly content.

Life proceeds at a different pace on the river, I remembered then, whether one is working or relaxing.

“I beg your pardon,” said the Mole, pulling himself together with an effort. “You must think me very rude; but all this is so new to me. So—this—is—a—River!”

“The River,” corrected the Rat.

“And you really live by the river? What a jolly life!”

“By it and with it and on it and in it,” said the Rat. “It’s brother and sister to me, and aunts, and company and food and drink, and (naturally) washing. It’s my world, and I don’t want any other. What it hasn’t got is not worth having, and what it doesn’t know is not worth knowing.”

- Kenneth Grahame, Wind in the Willows

|

| Illustration of Rat and Mole by E. H. Shepard |

Since I’d seen no car, I thought Charlie and Sandy must be away, but it turned out that Sandy was home, and after a while she joined me outside on the dock with her own coffee mug, and the two of us caught up on each other’s lives in leisurely fashion. I showed her my sketchbook, and she showed me her tiny portable watercolor kit, small enough to fit in a handbag, and after a couple of hours we walked up to Main Street and over to the Cove, a restaurant on the north side of the river, to meet her visiting grandson and his wife and their almost-three-year-old son for lunch.

I’d told Sandy about my missing billfold but was feeling no stress or panic. It would show up, or it wouldn’t. I had put a hold on the credit cards the day before, and although replacing cards and driver’s license would not be much fun, it was just one of those things. One foot in front of the other. Deal with it. That's life.

Am I calmer because I’ve learned not to panic? Or is it simply a lessening of energy that comes with age? Or am I become so calm, so unlike my younger self, because after losing the love of my life nothing else that happens to me feels all that difficult? Maybe all are partial explanations.

Later, back home, I dared to plant seeds for tender annuals and vegetables. Launched tennis balls through the air for Sunny Juliet. Searched one more time through my car for the missing billfold and contemplated necessary next steps if it didn’t turn up. But the day was too beautiful for worry. I’d mowed grass on Sunday, and my yard, fresh and green, was orderly and inviting as I puttered about the perennial borders, grateful for my Michigan country life.

|

| Sunny likes Michigan, too. |

And the icing on the cake was that I found my billfold in the grass, right there at home! Now I don’t have to think about that any more!

But have I been stingy with pictures of Sunny in this post? How about a recent scene at the dog park, Sunny and friends, with all dogs in happy motion. There! Satisfied?

|

| Dogs having fun! |