Fall, like spring and summer, is more continuous change than steady state. Maples and birches demand that we monitor their changes with our attention, it seems, while other trees and plants surprise us later, every year: deep carmine osiers, yellow asparagus, scarlet Virginia creeper, golden tamarack, and the buttered-toast-dripping-honey leaves of beeches.

Colors shout in the sunshine and gleam in the rain before fading almost imperceptibly against the darkening skies and winds that tear foliage from branches to leave them bare against the clouds.

Does autumn bring forth your wanderlust or tempt you indoors with cocoa and blankets and books? Perhaps it does both, and that’s when books of other people’s travels are so welcome. Armchair travel, vicarious adventure! Where would we be without it?

…Two brothers uprooting themselves to seek adventure or a better life together was a pretty typical Oregon Trail pairing, and our resemblance to the nineteenth-century pioneers was significant. Nick was an injured, unemployed construction worker in the midst of a deep recession in home building in Maine. As a print journalist I typified an American character type that had been familiar since the industrial revolution – the worker with redundant, antiquated skills displaced by technological change. We were going to see the elephant because there wasn’t much else going on for us at home.

- Rinker Buck, The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey

I’ll explain “seeing the elephant” in a minute.

First, though, I have to admit that when I picked this book up just after finishing Crazy Horse, by Mari Sandoz, I wasn’t sure I would find the story congenial. Not only does Buck open his story with some background on the Oregon Trail, but the map also showed me place names I’d encountered in the Sandoz book: Fort Kearney, Fort Laramie, Fort Fetterman. And reading of 400,000 pioneers, many of whom “would never have made it past Kansas” without the assistance of Native American guides, I thought of Crazy Horse and his friends, dismayed by disappearing game (disappearance that brought great hunger) but confident that the pioneers would keep moving, on their way to somewhere faraway. I also took exception to the author’s claim that this was the largest human migration in world history, having read so recently The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson, telling of the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North, six million people migrating over the period 1916-1970.

Still, the story of two brothers setting out is a story of our time, not history, and such an unlikely and challenging modern journey that I set my doubts to one side and read on.

The phrase “seeing the elephant,” new to me, was apparently one 19th-century pioneers used all the time. The “elephant” in letters and journals of the time seemed at first to refer to the hugeness of the plains, later to the dangers to life that crossing the plains involved, the great American adventure of its time captured and reduced poetically to its lowest terms in the malleable elephant cliché.

In the year 1958, while conventional suburban American children were gyrating with hula hoops in their backyards, Rinker Buck’s father took his family on an epic vacation. The author was only seven years old when the family set out on a 300-mile odyssey in a Mennonite wagon pulled by a team of draft horses, with a saddle horse tied on and following behind, traveling from an old New Jersey farm by way of old roads and historic sites of Pennsylvania and back home again, and that little seven-year-old boy was entrusted with the task of riding on ahead of the wagon in the late afternoon to locate a likely overnight campsite! What a dream! Who else but someone with this childhood memory would come up with a scheme to take a wagon and team of mules from Missouri to Oregon? And who else but a brother from that original trip would be so eager to sign on to such a crazy scheme?

So I know “where the story is going” geographically, but what may happen along the way I have no idea. Anyway, I’m hooked. Nothing like a wacky travel narrative for escape from the daily news cycle....

A busy bookstore is always gratifying to a bookseller, and my next-to-last Saturday in the bookstore was a busy one, but it’s a rare day that doesn’t allow dipping into some as-yet-unread book, and I’d had Michelle Obama’s Becoming set aside for several days. The very first pages of that book then hooked me, and a day later, having set aside the Oregon Trail for the First Lady, I was almost halfway through Michelle Obama’s story. What a refreshingly honest, down-to-earth, and yet thoughtful, absolutely elegant woman!

“They’re Chicago people,” the Artist reminded me (as if I might have forgotten). “They might very well walk into Dog Ears someday.” Wouldn’t that be something?

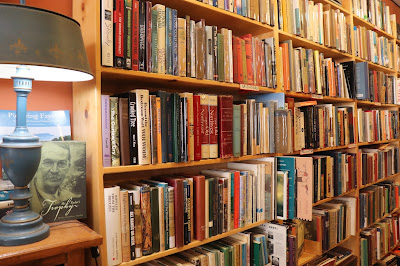

But now it’s Sunday, and I’ve come to Dog Ears Books myself for a couple of afternoon hours, because next Saturday, Halloween, October 31, will be my last bookstore of the 2020 season! What a weird, strange year it has been, in the book business as in every other part of American life (as well as life beyond our own shores). Usually open on May 15, this year it was July 1 before the store was open to public browsing and buying for other than special order customers. We have all had to mask up for in-person meetings, with friends and strangers alike. Manufacturing and distribution chains for books were disrupted along with so many others; special summer events were cancelled; some authors had new book releases pushed off until 2021. And yet we persisted! We went forward with what we had, which was (as always) plenty of wonderful old books and lots of wonderful new ones, as well. Everyone behaved very well. It was a good season.

Already I’ve had forward-thinking customers come in to stock up on winter reading, one man filling two whole grocery bags, others content with tall stacks of books. I welcome, wholeheartedly, all long-time and new customers this coming week! Many books here are calling out to go to new homes as holiday gifts (hint, hint).

I will miss you all in my bookstore during my months of seasonal retirement, but I’ll remind you now that there are other bookstores here Up North, and while I’m gone I urge you to "shop my 'competition.'” Really? Yes, of course! One thing I have always absolutely loved about being an independent bookseller (one thing among many, of course) is that we booksellers – real indie types -- do not generally regard one another as competition. Customers sometimes make reference to “your competition down the road,” but in our small, fiercely independent shops -- shops that reflect our own personalities and interests as well as the region where we live and work – we see and treat each other as colleagues. It is a collegial line of work. If we don’t have something in stock, we send the customer for that book to someone else’s shop, sometimes even calling ahead to see if the book the customer wants is on hand – which I did only yesterday, in fact. We’re all on a cordial, first-name basis. We know each other, and we like each other. We are real people. And we all want all the others to succeed.

So please buy new books from Leelanau Books in Leland, Bay Books in Suttons Bay, Cottage Book Shop in Glen Arbor, and Horizon Books in Traverse City. If you're a lover of old books, visit Landmark Books in Traverse City, and if Paul doesn’t have what you're looking for and you must shop online, here are some alternatives to the Online Behemoth.

Has the idea of an independent bookstore yet to become important to you? Take a look here. Community, curation, convenience. My place won’t be convenient while it's closed for the winter, but Dog Ears Books has always been about a curated collection, and our community commitment has only grown stronger over the years.

And we certainly expect to re-open Dog Ears Books in 2021 – I hope by May 15th. One thing I can safely say, after over 27 years in business, is that I have lived up to the promise I made an earlier Northport landlord long ago: “I’m in it for the long haul.” And in retrospect 27 years have flown by. -- Someone the other day wished me another 27, which is rather more than I wish for myself, but I do hope and plan to be back in 2021.

So come down to Waukazoo Street this week! We are here now! And really, isn’t that all that any of us can ever say with certainty?