Birds in Books

I picked up and began reading a biography of Gene Stratton-Porter, one of my mother’s favorite writers, and wished my mother and I could discuss the author’s life together. After a while it occurred to me that I sent this book to my mother, who read it and returned it to me to re-sell as a used book (my frugal mother!), and still I had not read it before myself. How illuminating to learn that Gene (born ‘Geneva’) Stratton-Porter was not only a popular novelist but also admired for her nature books (I had her Book of Moths once) by writers as famous as Christopher Morley, who likened her work on birds (she also loved and photographed and wrote about moths) to that of the work of another of my naturalist heroes, Jean-Henri Fabre, on insects. High praise!

In reading of her life and the agreement she made with Mark Doubleday to publish all of her work, exclusively, one nonfiction nature book for every novel (the fiction sold better, but Stratton-Porter was insistent on having her nonfiction published, as well, so the agreement was alternate years for each genre), I was surprised and delighted to learn that Mrs. Doubleday, Nellie, was none other than the writer Neltj Blanchan, author of Bird Neighbors; Birds Every Child Should Know; and The American Flower Garden. It is easy for me to imagine wonderful conversations between these two women naturalists and writers. Stratton-Porter was a devoted gardener all her life, especially devoted to wildflowers, from her Indiana childhood to her later years in California.

My mother fulfilled a dream when she and my father visited the Limberlost (though I think my father may have waited in the car while my mother made the tour), and I shall have to make the trip myself one day (she was always a stickler for “I shall”), as a pilgrimage in honor of my mother. It looks like a beautiful place to visit, anyway.

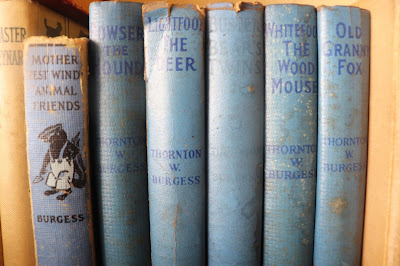

As it happens, I don’t have any of either Stratton-Porter’s or Blanchan’s nature books in stock at the moment, but I do have The Burgess Bird Book for Children, by children’s author Thornton W. Burgess, whose Old Mother West Wind series and other stories featured talking animals were so popular with child readers of the early 20th century. His Bird Book is told as stories, also, with dialogue between, for example, Peter Rabbit and Jenny Wren – “intended to be at once a story book and an authoritative hand book,” with illustrations by none other than famous naturalist-artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

Never a big Burgess fan myself, I appreciate the Fuertes illustrations more than the Burgess text, but I have had several Burgess fans among my bookstore customers over the years. Chacun à son gout, as my friend Hélène used to say.

Quick Bookstore Story

And now here, to change the subject, is a little story that is very Leelanau: One of our neighbors came by the bookstore on Monday and said he and his wife were going to pick up sandwiches at the New Bohemian Café and that he’d like to buy me lunch, also. Or I could join them down the street, “but there’s no indoor seating.” No problem, I said. Come on back, and we’ll have lunch at my big table. I moved books to make space, and halfway through our lunch my neighbor slapped his hand on the top of the table and exclaimed, “This is my parents’ old dining room table! You must have found it at Samaritan’s Closet” – a thrift store in Lake Leelanau, as had indeed been the case. “So many birthday parties we had around this table,” he said, and I was for some reason happy to know about the table’s former life and to think of it as progressing from birthdays to books, all here in Leelanau County.

Gotta love these little stories that connect us country people! And the Danish Modern furniture of the 1950s? Yes, I remember!

Another Quick Bookstore Story

This one you won’t believe. I can hardly believe it myself. My first customer of the morning on a rainy Thursday was a man from London, England. His wife is from Traverse City, so they visit every year, and he knows my shop well and goes right to his favorite sections. When he brought his choices to the counter, he said -- he really, really said this! -- “I have to tell you: This is my favorite bookstore.”

I thanked him, so pleased -- thrilled! -- that I didn’t press for more specific information. (Favorite in Michigan? In the U.S.? All-time favorite ever?) Don’t investigate a compliment too closely, I say. Just smile graciously and thank and let the glow warm you for the rest of the day.

Recent Books Read (Since Last Post)

The first one below was a novel I re-read. Fabulous! Love the Socrates Fortlow character and wish there were more books featuring him.

Mosley, Walter. WALKIN’ THE DOG (fiction);

Covington, Kathryn Rankin. THE RIPPLE OF STONES (fiction);

Roth, Michael. TIME BETWEEN SUMMERS (fiction/nonfiction);

Green, John. THE ANTHROPOCENE REVIEWED (nonfiction);

Lively, Penelope. TIGER MOON (fiction)

Peasy Report: A Milestone, a Message, a Sigh

The new wading pool wasn’t a milestone, but Peasy loves it. He loved splashing in his dog-friend Molly’s wading pool (bigger than the one he has, the only one I've found so far) after a long run-and-play session in the high desert, so when the weather warmed up (and it will again, I’m sure, despite the current cool spell) I figured he would love a wading pool of his own here in Michigan.

The milestone, however, is something different, and what made this particular red-letter event even more special was that it was practically a non-event. Did Peasy even notice?

A little background first --.

Peasy, like Sarah, is not nuts about being groomed. To brush him at all, I resort to a soft curry comb made for horses. It won’t do much when he starts shedding and needs his undercoat combed out, but he tolerates the brush and is becoming accustomed to having it used on him, which is more than half the battle.

Toenails, though. That’s another story. (Do you know any dog that likes toenails clipped?) My old Nikki was so submissive that she didn’t put up a fuss, but Sarah was a real rebel when it came to her feet, and that was Sarah, the practically perfect dog, who never had anything bad happen to her in her whole life! So what to do with a dog-boy who has had as many rough challenges already as Peasy in his young life?

Well, I am following the wisdom of Patricia McConnell on “reactive dogs” and that of Jean Donaldson, author of The Culture Clash. Rather than resort to a muzzle and a wrestling match (the alternative being outright sedation), I have been slowly and patiently desensitizing Mr. Pea to the clippers. I let him sniff them, I stroke his feet with them, I “clip” the air near his legs, and we’ve been doing that for a couple of weeks. Finally on Thursday morning I decided it was time to try following up the familiar routine with clipping a single nail.

He hardly seemed to notice! Good dog!!! I was so excited!

Working to desensitize a dog to reduce fear in situations the dog has long found frightening is a long, slow process. It takes a lot of patience. It’s time-intensive. But ask yourself: how long do you think you will be living with your dog? Why not take the time to make both your lives easier and more pleasant? I could say this message comes from Peasy, and if he understood about telling you what makes dogs happy, and if he had even noticed the milestone in his life, I know he would have sent this message.

Lest I mislead with partial information, however, I must admit that the dog with issues still has them. The other evening when I retrieved, from under a porch chair, a sock he had stolen and chewed up, he showed me his very scary, snarly, threatening-to-bite face. You wouldn’t want to see it, believe me. I opened the porch door and sent him outside to stay out by himself for ten minutes. We didn’t fight about it-- he just had a time-out. He was then his regular sweet self the rest of the evening. On the other hand, as I say, he had no meltdown over the nail clipper, so I think we are continuing to make progress. I hope so. It isn't always easy-peasy. This dog has issues -- but I believe he has a lot of potential.