by L. E. Kimball

Paper, $18.99

April 2016

L. E. Kimball first came to my attention in 2010, when Switchgrass Books, an imprint of Northern Illinois University, published A Good High Place. Set east of Grand Traverse Bay, with a story stretching from 1910 to the 1960s, that novel traced a difficult path of friendship in very particular and specific Michigan terrain. One historical thread involved an old tourist steamer that once ran the inland waterway of lakes and rivers from Elk Rapids north to Eastport; another wound its way to the old Traverse City State Hospital, originally known as the Northern Michigan Asylum.

Kimball’s new book is billed as “stories” but could as easily be labeled a nonlinear novel. Thus readers who prefer long forms of fiction will appreciate the fact that three main characters appear and reappear consistently throughout the book, while those with a love for short forms will be more than satisfied by each story’s ability to stand on its own.

The fact that several of these stories previously appeared in journals as different as Orchid, Alaska Quarterly Review, and Gray’s Sporting Journal should give some idea of what to expect from Kimball this time around. Yes, we are traveling yet farther north, over the Mackinac Bridge to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. We are going to be outdoors and off-road. There will be hunting and trapping and fishing and pickup trucks and campfires and forest fires. This is a saga of grandmother, daughter, granddaughter, three generations of U.P. women, along with the men who are their friends and lovers and sometimes their husbands – and, always, the land that tethers them.

Abandoned in the town dump outside Newberry at the age of one month and discovered by a couple who will become her adoptive parents, a baby girl is given the name Norna. She has survived overnight, protected by a discarded copy of the Newberry Gazette. Twenty years later she will learn about trapping and dressing and skinning game from an Indian man whose camp she shares one winter, and still later she will marry (someone else) and fall in love with Drummond Island, a place that, like her,

has a delicate skin upon which little will thrive, yet she is brutally rugged underneath that skin.

On Drummond, Norna turns from men to rocks. Stone is hard material. It can be carved. An independent life can be carved, also, but first Norna must trade island life for a return to the woods and rivers west of Newberry.

For many years, Norna’s daughter Aissa has a more ambivalent acceptance of the north country, captured in the episode when her mother takes her out to shoot her first bird.

It seemed like it took forever for Aissa to get the shells in the gun. Her hands shook and the gun wavered, and she even shuffled her feet a few times, which all seemed to take hours, but the bird sat there, apparently enjoying the warm sun on its back. Norna didn’t say anything more, but she’d moved behind Aissa next to her right arm and she nudged her. Aissa waited and Norna nudged her again, while Aissa felt waves rise to her chest, hard and unrelenting.

Impatient with her mother’s backwoods camp ways, Aissa marries Ben, a dentist, for his competent hands and the order she feels he will give her life. Like her mother, she too eventually returns to the old U.P. cabin, but not before making a wild cross-country trip in search of faith, undertaken after she realizes she has not only held things back from the men in her life but also from herself: “Joy and pain and demonstrable grief. Laughter.”

Jane, the woman of the third generation, becomes first a horse trainer and then a gourmet chef. Still, more like her grandmother than her mother, Norna thinks. But Jane also has a gift no one else in her family possessed: when in the company of the dying, she sees “glimpses” of the dying person’s life all at once, past in present, the pieces like a quilt, with the added complications of possibilities and “migrations.” People meeting her for the first time sometimes seem to recognize Jane.

She was familiar because she’d glimpsed bits of their pasts and she’d glimpsed bits of their futures as well – hovered over the continuum of their existences like a figure in a Chagall painting....

Back in 1989, Jim Harrison wrote, “Our essential and hereditary wildness slips, crippled, into the past” (“Meals of Peace and Restoration,” collected later in The Raw and the Cooked: Adventures of a Roving Gourmand, 2001). Whether you believe that or not – and it is undeniable that natural wild places are fewer and less accessible with each passing year – wildness remains blessedly alive and vivid in the work of our best Michigan writers. From Ernest Hemingway through Jim Harrison to Bonnie Jo Campbell and L.E. Kimball run untamed stretches of Michigan rivers, and in coming to know these rivers, fictional characters we recognize as friends come to know themselves and their place in the world.

In Seasonal Roads we find again Hemingway’s rivers, Harrison’s feasts, Campbell’s competent and independent women survivors – along with something else that is pure Kimball, something elusive, delicate, and poetic, and at the same time savage and strong.

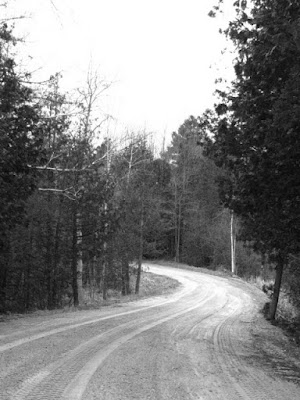

The road above, as you see, was freshly graded before our most recent snows. The publication date for Seasonal Roads was originally given as April 1, so I expected to have the book in stock by now but am still waiting -- impatiently waiting, the same way we here Up North are still waiting for spring.

No comments:

Post a Comment