|

| View from the first juniper -- |

My previous post told of a climbing adventure Sunny Juliet and I had on Saturday morning after I admitted that, before our adventure, I had “gotten up on the wrong side of the bed,” as my parents used to express morning crabbiness. Returning to the cabin post-adventure, then, with no possibility of a coffee house visit in town, would I also return to crabbiness? That was the big question! I had no social plans for the day, and no plans for further adventures, so the danger was real. I busied myself by starting to cook a pot of lentils to stave off bad temper, but the success of this plan would depend on the success of the lentils….

Ah-ha! Suddenly I remembered that the day was Saturday, not Sunday, and that meant there might be something in my mailbox down the road! Purposely stretching out the period of anticipation, however, I chopped onion and carrot to add to the lentils, adding also dissolved tamarind paste, Better than Bouillon (chicken flavor), and plenty of curry powder. Swept the floor. Picked up a book.

|

| I love USPS, and they do an excellent job here! |

Because, you see, if the mailbox is empty on Saturday, all hope must be deferred until Monday; but until my key unlocks the box, hope can imagine a happy outcome. Is Schrodinger’s cat dead or alive? Is my mailbox empty, or does it hold a surprise to gladden my heart? Possibilities exist, if only in the mind, until a box is opened, so why hurry, since one possibility is always disappointment?

(Please note I do not say the mailbox was both empty and containing a surprise, any more than I say the cat in Schrodinger’s closed was both alive and dead until the box was opened. This frequent interpretive error of a famous argument in physics is made by those who do not recognize the argument as a reductio ad absurdum. Thank you very much!)

Cut to the chase. Waiting for me on Saturday was not emptiness but a book I had ordered from Midtown Scholar Bookstore in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. (Note: When I order online, I always try to order from real bookstores.) Carry the package back to the cabin. Remove brown cardboard. Next, open the book! Again, a range of possibilities presents. Will I be made happy? Disappointed? Left indifferent?

Flashback. One or two friends had posted links on Facebook to the personal home library of the late Dr. Richard Macksey, humanities professor at Johns Hopkins University. Seductive images of the library made me want to know more about Richard Macksey, and after I’d read about his life and work, naturally I wanted a book he’d written, which is how this particular volume came to be in my mailbox on Saturday.

|

| Not one you would have chosen? |

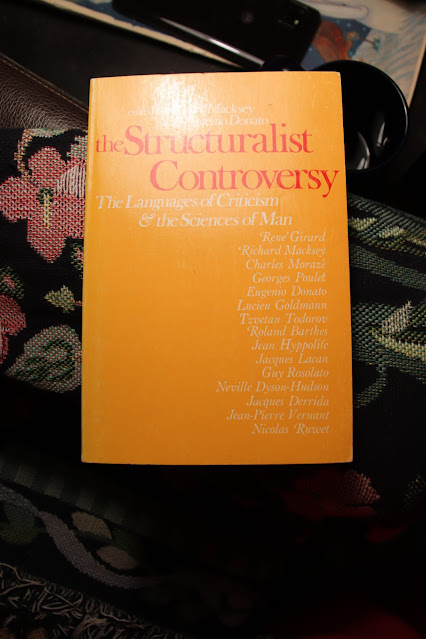

The book. What I found at Midtown Scholar was a paperback edition of the proceedings of an international symposium on structuralism convened at Johns Hopkins in 1966 – not only papers presented but discussion following each presentation – with, thanks to Richard Macksey, an all-star multidisciplinary cast: René Girard, Richard Macksey, Charles Morazé, Georges Poulet, Eugenio Donato, Lucien Goldmann, Tzvetan Todorov, Roland Barthes, Jean Hippolite, Jacques Lacan, Guy Rosolato, Neville Dyson-Hudson, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Pierre Vernant, and Nicolas Ruwet, to give the names in the order in which they appear on the book’s cover. The book itself is The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism & the Sciences of Man.

Reminder and disclaimer. I was never an English major, please recall. Reading literary and art criticism can put me off, and writing it (I learned early on, when given such an assignment, not to choose work I loved!) I found downright painful. One graduate class in Philosophy of Literature and a semester as a teaching assistant in Philosophy of Film, with another in Philosophy of Art – that is the extent of my formal background in criticism. Graduate classes in philosophy in the late 1980s, however, introduced me to Foucault and Derrida, structuralism and deconstruction. But that’s all, and it was not a road I traveled very far.

Back to the book. Richard Macksey’s opening remarks to the assembled group bore the title “Lions and Squares.” It was – I suppose predictably and appropriately – academic, historic, and jargon-studded. It was fine. It did the job. My heart was not set on fire, but neither did I regret having ordered the volume. I read on….

I should probably re-read, “Tiresias and the Critic,” presented by René Girard, and before doing that should re-read Oedipus Rex, but as there was no discussion following that short piece, I moved on to Charles Morazé on “Literary Invention,” in which he proposed to question “the relationship of literary invention to invention in general.” Both the paper and the discussion following leaned on a distinction between invention and discovery, and I found myself smiling at the discussion, so familiar from my graduate school years. I was reading happily, crabbiness banished.

Jackpot!

Then came “Criticism and Interiority.” At first the paper’s title gave me a sinking feeling, a feeling that could be named the “Anticipation of No Fun at All.” How wrong that prediction was, and how glad I was to have been wrong! Why was I never introduced before to Georges Poulet? Here is how he begins:

At the beginning of Mallarmé’s unfinished story Igitur there is the description of an empty room, in the middle of which, on a table, there is an open book. This seems to me the situation of every book, until someone comes and begins to read it. Books are objects. On a table, on shelves, in store windows, they wait for someone to come and deliver them from their materiality, from their immobility. When I see them on display, I look at them as I would at animals for sale, kept in little cages…. They wait. Are they aware that an act of man might suddenly transform their existence? Read me, they seem to say. I find it hard to resist their appeal. No, books are not just objects among others.

This man is speaking my language! And while his position becomes increasingly complicated as he proceeds, I was with him all the way. He speaks of how, when we read, the mind of the author enters our own. We think the writer’s thoughts – or they think us – but we are not thereby invaded. No, in the intimacy of reading, “I begin to share the use of my consciousness…” as the author and I “…start having a common consciousness.” From his personal experience, Poulet says,

Thus I often have the impression, while reading, of simply witnessing an action which at the same time concerns and yet does not concern me. This provokes a certain feeling of surprise within me. I am a consciousness astonished by an existence which is not mine, but which I experience as though it were mine.

Haven’t you felt this, too, at times? “Lost in a book,” now and then you remember that you are reading, that you are not the character with whom you identify or the author of the characters, that you are holding in your hands a physical object, a book, and that the words on the page are creating visions in your mind. Really, it is astonishing, is it not?

I will not attempt a complete exposition of the ideas in Poulet’s paper, as I’ve probably lost 95% of my readers by now, anyway, and you few stalwarts hungry for more can treat yourselves to reading his works firsthand. But first, just a little more, because I find this so delicious. Poulet draws a contrast between two kinds of critics, one who loses their [you see? I can use current pronouns, though it still goes against the grain!] own consciousness in that of the writer, the other who refuses such identification altogether. The first kind of critical thought (I might say ‘reception) he calls ‘sensuous,’ the second ‘clear.’

…In either case, the act of reading has delivered me from egocentricity. Another’s thought inhabits me or haunts me, but in the first case I lose myself into that alien world, and in the other I keep my distance and refuse to identify. Extreme closeness and extreme detachment have then the same regrettable effect of making me fall short of the total critical act: that is to say, the exploration of that mysterious interrelationship [my emphasis added] which, through the mediation of reading and of language, is established to our mutual satisfaction between the work read and myself.

He then suggests – perfect, I say! – combining the two methods “through a kind of reciprocation and alternation,” and I am delighted! Well, there is much more about subjects and objects, subjectivity and objectivity, but I leave it to you who are interested to follow up with primary sources.

The first question asked of Georges Poulet in the discussion that followed his presentation was how, if at all, reading was to be differentiated from understanding another’s speech, and while acknowledging the fundamental similarity in the two cases, Poulet pointed out that in conversation, two or more participants are not only listening but also themselves speaking,

…and when we speak, we don’t listen. Thus very often, conversation, instead of becoming an inquiry in which someone who listens (or who reads) strives to identify himself with the thought of someone who speaks (or writes), becomes instead, quite to the contrary, a sort of battle….

Here, now, re-reading, I pause. [Pause. What do you think?] Because when I read history or opinion of any kind, I read not to lose myself (as in reading a novel or a poem) but as if I am a participant in a conversation, agreeing and disagreeing, questioning, objecting – in short, definitely keeping my distance. As when I read this very paper! But this is not a major disagreement….

Only one more bit that I can’t stop before including: In response to a philosophical question from James Edie, Poulet addresses an implied side issue:

Am I “for” or am I “against” structuralism? I simply do not know; it is not for me to say; it is for the structuralists themselves. For my own part, sometimes I feel rather alien to the abstract and to the voluntarily objective way in which these structuralists express their own discoveries, and sometimes I am even shocked by that position. Sometimes I am shocked especially by their air of objectivity (I think particularly of one of them whom I consider a friend). I am particularly shocked when he claims to arrive thereby at scientific attitudes. I must confess that, to my own mind, very clearly, very definitely, criticism has the character of knowledge, but it is not a kind of scientific knowledge, and I have to decline very strongly the name of Scientist. I am not a scientist and I do not think that any true critic when he is making an act of criticism can be a scientist. [Again, the emphasis added is my own.]

Well, my love only deepens with the statement quoted above. Not all knowledge should be called science, and science does not exhaust all the possibilities of knowledge. Thank you, Monsieur Poulet, for knowing so clearly where you stand and for allowing me, in reading your words, to stand with you!

And, once again, I echo fervently the words of the fictional Roger Mifflin, “Thank God I am a bookseller!” Magic and mystery are on every page of every book!

Postscript on Wednesday:

State of the Union address: I listened and was very, very proud of President Biden, both for what he said and how he said it. At the same time, I couldn’t help remembering that last year David and I listened together, and that brought tears to my eyes. Several times the president made a joke, and I thought of how important a sense of humor was to David, in his friends and in anyone who intersected with his life. I also noted times when we both would have said, “Yes!” to the president’s statements. (Unlike me, my husband always listened quietly to political speeches, saving his comments for afterward, so with him I tried to do the same.) I remembered how David’s opinion of the president (make no mistake: we both voted for him!) rose considerably after the State of the Nation address. This year again, the president showed dignity, strength, and resolve. He did not avoid controversial subjects, either. The office of the president is strong and honorable under this president.

Throughout the year, President Biden is not always in our faces from one day to the next and acting like the “great and powerful Oz." No, he is a team player -- but he is also a strong leader, and when he does speak out, he speaks out strongly.

David, I miss you! I wish we could have listened together again this year! Hope for my country, hope for our grandchildren and great-grandchildren — that’s what I got out of President Biden’s State of the Union address, and I know I am not alone.

|

| Keep calm. Carry on. |

3 comments:

I found your commentary more than a little bit interesting.In fact,I found it insightful!!!!

Whew! You have an amazing mind!

Well, I am going on with the rest of the papers but not with the excitement Poulet's gave me. He will be the book's highlight, I'm pretty sure.

Post a Comment