It will never be possible to get a completely accurate and unbiased account of the Barcelona fighting, because the necessary records do not exist. Future historians will have nothing to go upon except a mass of accusations and party propaganda. I myself have little data beyond what I saw with my own eyes and what I have learned from other eye-witnesses whom I believe to be reliable . . .

This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world. After all, the chances are that those lies, or at any rate similar lies, will pass into history . . . The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future but the past. If the Leader says of such and such, “It never happened” — well, it never happened. If he says that two and two are five — well, two and two are five.

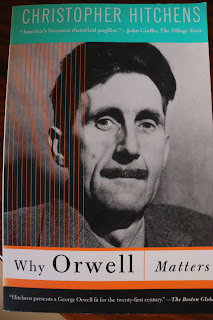

- George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, quoted in Why Orwell Matters, by Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Hitchens says of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia that it remained “an obscure collector’s item of a book throughout Orwell’s lifetime.” Not, in other words, a bestseller or anywhere close. Why would this be so? The answer given by Hitchens, one that makes complete sense to me, is that both the official and the popular views of the war in Spain relied on what I call a “two sides” formula. You know, the way we are told and so often tell each other that it’s so important to hear both sides of any issue or story? As if there are only two versions, the two clearly distinct from each other? That’s certainly the way the war in Spain was framed — as a conflict between conservatives (Catholic Nationalists, they called themselves; others called them Fascists) and communists (although some were grassroots socialists and others Stalin’s forces). Given the frame, which side any particular person saw as good and which as bad depended on that person’s ideological commitments rather than on more complicated facts, let alone whole truth.

One must close one’s eyes to the virtues of one’s opposition in order to construct an inhuman enemy.

Orwell was on the ground in Spain, an active fighter on the Left but also a man who saw clearly, first-hand, the way the anti-fascist revolution was betrayed by Stalin’s ruthless subversion of forces fighting for Catalonian independence. What were his options when he realized what was really going on? Stay with a local, independent Left and be tortured, even murdered by Stalinists for not being a loyal Communist? That happened to others he knew. Go with the Stalinists, the internationally recognized Communists, and betray the revolution or switch sides and become a Fascist? Neither of those would have been Eric Arthur Blair, a.k.a. George Orwell.

He chose to escape and tell the story, but it fell on deaf ears. The world had chosen sides, each one saying, “With us or against us!” Thus, one could only be seen — by the “other side” — as Fascist or Communist.

Sound familiar?

Here’s an irony for you: not only did Orwell back then have those on both the Left and Right who hated him — he also has admirers on both sides today. Today’s liberals are sure he was warning against the dangers of fascism, now imminent, while today’s conservatives say he warned against socialism, their especial bugaboo. Everyone wants to think Orwell was singing their song. Hitchens takes a chapter each show that both groups are wrong and can only turn Orwell into their saint by cherry-picking their quotes, but that’s all more than I am going to try to summarize here. You’ll have to read Why Orwell Matters for yourself— and then go back and read Animal Farm and 1984 again. One thing is certain: Orwell was warning the world about future dystopian possibilities.

One of several things that frustrates me about debate, in general (consequently, also about the adversarial American justice system), is the usually unquestioned assumption that there are always and only two sides to a question and that one one of them — and only one — is true, thus the other false. From the assumption, it follows that positions taken must possess the form of affirmation/negation: I’m right, you’re wrong. To acknowledge that there is anything to be said for one’s opposition is seen as weakening one’s own case, giving “comfort to the enemy.

Recognizing a much more complicated truth, Orwell in his day was caught in the crossfire. The same thing happens today in our country to many politicians who don’t adhere to a strict party line. Determined to vilify those with whom they disagree, Americans seem willing to give up truth. Why?

"Power is not a means; it is an end.

"… The object of power is power."

- George Orwell, 1984

I once had lively discussions on ethics and politics with a graduate school friend who had been the first woman in Ethiopia to graduate from university with a B.A. in philosophy. Our very different undergraduate educations, as well as wildly divergent life experiences, inevitably resulted in very different views at the opening of each discussion. But it was, each time I looked back afterward on the course of our conversation, energizing and delightful to realize what had taken place as we argued. I cannot remember a single time when one of us claimed victory and the other admitted defeat. Instead, by the time we had hashed through our subject for several hours, we always came to a more nuanced understanding of the issue at hand, an acknowledgement that black-and-white could not contain it at all, with the result that the two of us, together, now agreed on and occupied a new, third position not envisioned in our initial disagreement. Such a result would fall far outside the parameters of the rules of debate. It would not have made, for either of us, a big splash in professional academic philosophy circles, either. But we felt satisfied that we had both advanced toward truth in those discussions, as well as finding common ground. While it should not be impossible, in principle, to achieve similar results in the halls of Congress — if Congress were actually functional and all members focused on getting work done — it seems to have become nearly so in recent years.

Future historians will have nothing to go upon except a mass of accusations and party propaganda.

- George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia

As far as I’m concerned, that single sentence from the passage that Hitchens quotes is sufficient to establish that Orwell still matters today. His is a warning we would do well to understand and heed.