|

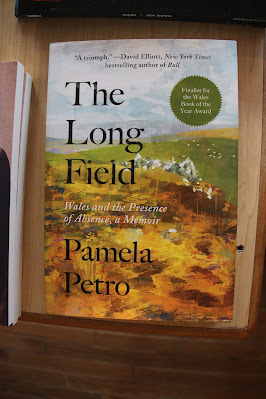

| My desk in December |

When we arrived at our ghost town hideaway for the winter, I made notes on the route we’d taken west and the places we had stayed: Kalamazoo, MI; Springfield, IL; Sedalia, MO; Wellington, KS; Dalhart, TX; Alamagordo, NM; and finally here, Dos Cabezas, AZ, 15 miles southeast of Willcox, AZ, and about 25 beautiful, winding miles west of the Chiricahua National Monument. The first page of the same composition book was already taken up with lists of things to pack (one list for the humans, another for the dog), and it was only on our second morning in the ghost town that I began keeping a sketchy narrative history of our season here. Back then, happy to be settling in for a few months under a sunny sky filled with wintering sandhill cranes, I had no idea that my notebook would become, in time a plague journal!

I always read a lot of books during our Arizona winters … write letters … blog about my reading and about our Cochise County adventures and explorations. It just happened that this year, for the first time, I also began keeping a journal. I certainly didn’t anticipate that I would be recording historic events; I merely wanted to fix everyday small details on paper. Because those little everyday details, the stuff of short-term memory, are easily lost as days slip into the past, and my time here is precious to me. I want to be able to hold the days in my hand as it were, and look at them again and again when I am far from these mountains and this desert.

|

| Winter morning |

So most of my mornings began, starting in December, with a session of journal-writing. The weather (no, it isn’t boring), social engagements, personal happenings (getting keys to the mailbox is a big deal to me), daily errands, and descriptions of surroundings flowed from my pen, along with re-emerging childhood memories and a few observations of the current national political scene. Quite a lot about hearing coyotes, through the night and in early, still-dark morning. A few notes on books read.

In short, nothing particularly earth-shaking. And that’s how it went, week after week.

… Sandhill crane count … first visit to the Smile4Jesus Thrift Shop … tales of my husband’s new friend in Willcox, the one I call the Born-Again Bear … brief accounts of dreams (very few remembered long enough to write down) … walks and hikes with neighbors.…

There were only a few words on the impeachment, although I thought it would never end … and very little on presidential campaigns, debates, caucuses, as I tried to keep attention on politics to a minimum … much more on my volunteer mornings at the library bookstore and the elementary school in Willcox. Of course, the political issues bled in from time to time, from impeachment to debates to caucuses to the State of the Union, because that was the news, nonstop, on the radio and television, but I tried to keep my attention locally focussed, as much as possible, escaping from the news to the outdoors.

People I love found their way onto the pages. One of my sisters was in Mexico for two weeks. The other went through the pain of losing an old dog. We spent February 15-17 in Tucson and anticipated a return in March. The Artist had a birthday. Then in late February, my former husband, the father of my only child, was moved (after only three days) from hospital to hospice, where he died a week later, and my son and I began spending daily time together on the phone.

In the larger world, a few of the Democratic hopefuls began to drop out of the race for candidacy, but too many yet remained, and far from business and home responsibilities in Michigan as I was, I found the world crowding in, events racing along, piling on top of each other without time to catch a breath. In many ways, the world seemed all present, minute by minute.

Yet only on March 10 did coronavirus come into my journal, when I noted that the Tucson Festival of Books, scheduled for March 14-15, had been cancelled the day before, adding at the bottom of that page: “Politics and coronavirus — our world today.” Two days later, March 12, I recorded that the president had announced, the evening previous, a ban on travelers from Europe, Ireland and the U.K. excluded. We began hearing daily about the terrible situation in Italy. COVID-19, the virus was now called. Less than two weeks ago. And yet now, March 20 as I am composing these thoughts, just past the spring equinox — such a short time since we were first told to stock our pantries for a possible two-week emergency quarantine — almost all universities and public schools are closed, churches have stopped holding services, restaurants all over the United States are open for take-out only, grocery store shelves are near-empty in key aisles (paper products, soaps and cleaning products, the dairy case), and more and more Americans, even those not yet on “lockdown,” are “sheltering in place,” even if they have not put themselves under “self-quarantine.” That is our national language now.

Still, though all of us are affected, each of us is experiencing these days of isolation differently. We are spread out across a very large country, and while some friends find themselves alone, far from family and close friends, others see their households expanding with schoolchildren and college-age sons and daughters home all day. I lost my volunteer jobs, but many other people have lost paying jobs, jobs they needed for basic food and shelter. “Lucky” ones see their savings “evaporating before our very eyes,” while the homeless appear at intersections, holding up cardboard signs. No one can hope to remain unaffected, from the most expendable part-time hourly wage worker to the most pampered trust fund baby whose investment portfolios has plummeting in value.

Here’s another personal note, this one I know shared by many — the strange realization that, simply because of our ages, the Artist and I are in a “vulnerable” group, members of an “at-risk” category. It was already strange enough just trying to get it through our heads that we are no longer young — hell, no longer middle-aged! — we still can’t fully believe that! — and now we are also particularly “at risk”?

For me, personally, there is the added strange feeling of being disconnected, physically, from the world that has been mine for almost 27 years, i.e., the world of books. I am not, after all, in my Northport bookstore, weighing the question of whether to entirely for the duration of the crisis or stay open to process phone and mail orders, make sales through the front door (or deliver books to local customers), and gratefully accept whatever help my little community might offer, along with doing what I might do to help the community. I’m not there. Instead of being “on the front lines,” as it were, I only read each day in Shelf Awareness what is happening with other bookstores around the country. So peculiar and unsettling! My feeling must be something like what my sister felt when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans just after she had moved away, that feeling of I should be there! Then added to that the uncertainty of not knowing if we will even be back in early May as planned — if that will be possible at all.

That’s part of my story. Everyone else has a story, too, quite different from mine. The general point I’m making is that each of us is having a unique subjective experience of these times, which means that together we will have a staggering number of stories, coming from myriad different vantage points, looking through lenses offering a kaleidoscope of perspectives.

So, are you keeping a “plague” journal? Years from now, what will you remember? What is strangely ordinary about this time for you? In what ways does the crisis seem real or unreal? What other times of crisis does it call to your mind? How is it unlike anything else you’ve ever experienced?

What books are you reading, and what kinds of meals do you find yourself putting together? Are you able to get outdoors for fresh air and exercise? Do you listen or watch or in some way follow news compulsively, every waking minute, or do you ration what you let into your consciousness each day? Do you sleep through the night or lie awake? If you sleep, what do you dream? If awake, what are your thoughts? How do you seek out comfort, and what gives you comfort?

With how many other people are you “sheltering in place,” and how is that going? Are you spending more time on the phone, calling and texting, or on your computer, e-mailing and following friends’ posts on social media? Do you feel more or less connected to those you love? Differently connected?

What is the best and worst aspect of this time for you? I should add so far to that previous question, shouldn’t I? Because we don’t know yet what will be the best and worst in the days and weeks ahead.

When I look at my own handwritten journal and see that I only used the word ‘coronavirus’ there for the first time ten days ago, I can hardly believe my eyes, but there it is on the page, although subjectively, right now, it feels like at least a full month that we have been obsessed with this news, every waking minute, to the exclusion of almost all else. I know I heard the news from China before March 10, but at that point, as the absence of it in my journal illustrates, the danger must have seemed very remote, a foreign problem only. That’s how fast everything has been happening.

Friends, I see some of your posts on Facebook, but those “news feeds” will be superseded overnight, you know, by whatever comes next, and even a year from now we will have a hard time remembering exactly when and now the pandemic (another frequently occurring word these days) first touched us personally. And besides, as long as you are “sheltering in place,” wouldn’t you like to use some of your time to make a lasting record for yourself and those who come after you? In all human lives, there are watershed events, some personal, others part of a national or world-historic fabric, and this is one of those times that will stand out whenever, in future, we look back on our lives. If you don’t see yourself as a writer, maybe you can keep a scrapbook or a photo album or make a quilt of “plague times.” We don’t have to be greedy opportunists to find opportunity in crisis.

What stories will you have to tell years from now?

|

| We each see the world from our own little corner.... |