The American Booksellers Association (ABA) is wrestling with an unwieldy and difficult issue these days, and, like any other ‘community,’ finds itself short of clear consensus. Let’s start with the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Recently a decision was made by the ABA Board (I hope I have the correct attribution here) to qualify the organization’s support of free expression as follows:

ABA does not favor the protection of free expression when it comes to speech that violates our commitment to equity and antiracism, i.e., racist speech, anti-Semitic speech, homophobic speech, transphobic speech, etc.

Response from members has been strong and mixed. I should mention here that I am not an ABA member only because my bookstore’s inventory is tipped more in the direction of used than of new books, and I found myself during the year I was an ABA member drowning in shipments of brochures, posters, banners, and other promotional material for new books, almost all of it designed for larger, new-only bookstores with dozens of employees. That being the case, I let my membership lapse with the explanation given here but have continued to follow in my daily e-mail Shelf Awareness newsletter news of the bookselling and publishing world, including political issues impinging on that world.

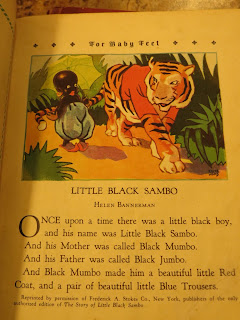

I have written on the subject of censorship before and have given: my general position; my response to one very specific brouhaha; and my take on what has been called

“financially-induced self-censorship,” or what I called in my post “indirect” censorship.

In response to ABA’s recent qualification on protection of free expression, one bookseller from Utah, Betsy Burton, is horrified. She writes:

Who decides which books to protect and which books not to? What standards do they employ to decide? What does the ABA intend to do with books that they have deemed unfit?

a. Ban them?

b. Burn them?

This might seem an Orwellian sort of reductio ad absurdum. And in one way it is. Because there is no rational answer, at least if one believes in the First Amendment. Either protect all books or throw the First Amendment out the window.

Forgive me for repeating myself here, but I am not a member of Congress. I am a bookseller. When I choose not to stock a particular title, I am not calling down U.S. (or even state) law to forbid the publishing, selling, buying, or owning of that title. Constitutional protection remains in place.

What, though, about the bookselling organization’s statement? Had I been on the board and required to vote on the substitution of a qualified statement for the First Amendment statement, I honestly don’t know how I would have voted, but what is clear to me is that the ABA statement has no force of law behind it. Even members of the organization -- and, as I have explained, I am not a member, for purely nonpolitical reasons -- certainly retain Constitutional rights to order, stock, support, publicize, and sell whatever books they choose.

The owner of any bookstore (and this would apply to large chains, as well) must always make choices, because no bookstore can stock every existing title. The smaller the bookstore, the more carefully such choices must be made. And, generally speaking, the more personal such choices will be.

My bookstore is a reflection of my values, which doesn’t mean that every book on my shelves is a reflection of my own opinion, because yes, I do value a diversity of opinion, but no, I do not feel obligated to support within my doors opinions that I find morally offensive. A bookstore is, of necessity, either a curated collection or an impersonal hodge-podge, and I like to think that mine is the former. I have, for instance, more books on agriculture and natural sciences than I have science fiction and fantasy, and that is solely a reflection of my personal interests, not a decision made on principle, but every new book I order is a choice I make. For me, it’s personal, and as long as I’m in business my choices will be mine to make, and they will continue to be personal.