I live in northwest lower Michigan, but for me that is not a single place. My official homestead residence is in Leelanau Township, the northernmost of our county’s township divisions. Tell that to my new phone, though! It keeps identifying my photographs near home as having been shot in Leland Township. Wrong! Trust my camera and me instead: the camera doesn’t try to be smarter than I am.

I live in an old farmhouse with a dog, but I also live outdoors (with the dog), working in the yard, going for long walks, noting the passing seasons in signs like the ripening of chokecherries and the way Queen Anne’s lace blossoms curl up into little brown birds’ nests come late summer.

During my working days, I live in my place of business, of course, the bookstore that was 30 years old in July. It wasn’t always in the same location (I’ve been in four different buildings in Northport), but whenever it’s moved I have kept the basic arrangement of books more or less the same, so there is a familiar continuity from one place to the next, and my current location has been home to Dog Ears Books since – can it really be since December 2006? Seventeen of my 30 years???

On a long drive across several states, a vehicle becomes a “mobile home,” even if it’s only a two-door sedan. A van, of course, holds even more, and on a good trip one comes to live in it (or two or more live together in it) with the feeling of being at home even when not stationary (though some days are more comfortably homey than others). Over our years in Leelanau County, the Artist and I enjoyed many a “county cruise,” as he liked to call our Sunday expeditions or slow summer evening drives down to Maple City for pizza or Cedar for ice cream. We could have found pizza and ice cream in Northport, but after being in situ all day we enjoyed the leisurely changing scenery of favorite back roads, and we sought out horse farms for the pleasure of seeing beautiful animals.

But (my point is that) wherever the Artist and I were together felt like home to me. There was one unhappy night during our otherwise joyous time in France when we wished ourselves elsewhere, but that was due to a flat tire in the rain on a narrow road and a strangely (uniquely) unsatisfactory meal. By the time we ditched the offending rental car in Fontainebleau the next day and were on the train back to Paris, everything was fine, and once back in Paris, we were “home” again. Here is an old post I found with thoughts on travel and home.

During winters in Cochise County, Arizona, the Artist surprised himself one evening when we returned to the cabin and he remarked, “It’s good to be home.” It was only a rental, but over time it filled with our own things – art on the walls, bookcases filled with books, kitchen items and linens and cowboy boots and hats picked up here and there – so that it did, indeed, come to feel like home to us. We had routines there, we had pleasant neighbors….

All earthly homes, after all, are temporary, are they not?

Anyway, as you know if you’ve read this blog before, (and as you might guess, anyway, knowing that I have a bookstore), I also live in books. Recently reading Horse, by Geraldine Brooks, I lived multiple lives stretching from 1850 to 2020, and now, nearing the last pages of Confederates in the Attic, by Tony Horwitz, late husband of Geraldine Brooks, I am traveling through the South and meeting people I never would have met in my own “real” life. Both these books have my highest recommendation. I’m not sure everyone would respond to them exactly as I did, however.

Would other readers tremble as they turned the pages of Horse, and would their eyes fill with tears, not only over certain passages when a human or equine character is in danger or difficulty but nearly all the way through the book? And was my reaction influenced by the knowledge that Brooks had begun the novel before her husband’s sudden, unexpected death and finally returned to it as she worked through her grief at his loss? Ah, but I loved the story, and not only for its horsiness, though that was certainly part of the appeal.

At least one reviewer felt that the author had made the characters of Jarrett and Theo, both young black men, too good. As a white female writer (Australian to boot), Brooks knew some people would fault her for trying at all to portray the inner life – thoughts and feelings – of black men, particularly the 19th-century life of enslaved Jarrett but also that of modern mixed-race Theo. But if writers only wrote characters like themselves, literature would be a rather barren field, wouldn’t it? And isn’t it strange that fictional characters might be seen as too good?

I can’t help feeling that the “too good” judgment says more of our times than of the author’s choices. There are many kinds of heroes in literature, after all, and not all have to be tragic heroes, brought down by a tragic flaw. They certainly don’t all have to be anti-heroes, either, I hope! Read through this list and see – if you’ve read Horse, and if you haven’t yet, then get on it right away! – what kind of hero you might call Jarrett or Theo. Or not heroes at all? Then, why not? Another question here: Does the 21st century accept everyman or classic heroes only in fantasy fiction? That seems sad.

In Confederates in the Attic, Tony Horwitz tours historic Civil War sites in ten states and learns just how alive the Civil War still is for many Southern groups and individuals, their cast of heroes and villains very different from that of Americans in other parts of the country. That is, while I don’t recall being taught in my Illinois education that any of historical persons of the 1860s (other than anonymous slave-holders) were exactly “villains,” Illinois as the “Land of Lincoln” certainly saw Abe as a hero and martyr. Yet I always had my doubts about Sherman’s march to the sea, which appeared to me somewhat like America’s dropping atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the argument in both cases being that the wars came to a close sooner, thus saving soldiers’ lives. Killing civilians, including children, to save men in uniform, though, never sat right with me. And who knows when or how the Civil War and World War II might have ended without those civilian atrocities?

Joseph Campbell, in Hero With a Thousand Faces, identified a universal hero myth, in which the protagonist leaves home, has transformative adventures, and eventually returns, changed and triumphant. I wonder about this. I’ll go along with the adventures – challenges to be met, adversities to be overcome – but is life really that much like baseball, with return to home plate the only possible good outcome? I see that homecoming can be a good way to bring a life to wholeness, but I question whether or not it is the only way. Some of us whose families have not been established in the same place for generations are fortunate, as I have been and as John Denver was, to “come home” to a new landscape and to create memories there in whatever time we have.

One man Tony Horwitz spent time with, in a little Southern crossroads called Sutherland Station, lived in the same building where he had been born. It had been a general store when his parents were alive.

We sat on the porch, spitting watermelon seeds and watching traffic pass on the busy new highway bypassing town. I told Olgers about my journey and asked why Southerners like himself revered the past. “Child, that’s an easy question,” he said. “A Southerner—true Southerner, of which there aren’t many left—is more related to the land, to the home place. Northerners just don’t have that much attachment. Maybe that means they don’t have as much depth.” He paused, then added, “I feel sorry for folks from the North, or anyone who hasn’t had that bond with the land. You can’t miss something you never had and if you never had it, you don’t know what it’s all about.”

Someone who has never traveled 100 miles from home, I guess, can be forgiven for imagining that people in other parts of the country are not attached to their home ground. Certainly Wendell Berry has a bond with the land of his Kentucky farm, but I know people here in Leelanau County, farmers or not, with similar feelings. “I’ve come home,” one young woman told me just the other day. She had lived away for a few years but has returned now to the house her grandparents lived in when they farmed the land. And the now-vanished log cabin site I visited only the other day housed an early generation of a family many of whose members (though not all) lived and died not far from those beginnings.

My personal story is that of more restless Americans: father born in Ohio and mother in California, they married in Chicago, and I was born in South Dakota, later to grow up in Illinois where my younger sisters were born. Our family started camping in Michigan when I was 12 years old, though, and when I was 18 it became my home and has been ever since, despite my love for France and a more recent romance with the mountains of Cochise County, Arizona. “I can’t imagine not living in Michigan,” I told our grandson when he asked if I might someday want to move permanently to Arizona.

The catalpa trees that have appeared on their own and grown since the Artist and I began living in the old farmhouse, apple trees I planted that now bear fruit every year, old maples and basswood planted by the original owners, as well as smaller discoveries, some of them new in the past couple of years, like young hawthorns and exciting wild ginger – all of this, along with every road in the county, spells home to me and is redolent of priceless memories.

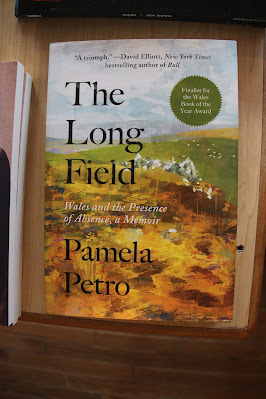

I look forward to reading very soon Pamela Perro’s The Long Field: Wales and the Presence of Absence, a Memoir. That phrase “presence of absence” certainly speaks to me. My more specific expectations of this book I will save for another time, however, when I have read it and can report on what I found in its pages.

Thank you for being with me today, on whatever “today" you are reading these words.