What books were being given

to boys and girls as Christmas presents in the year 1928? Many probably

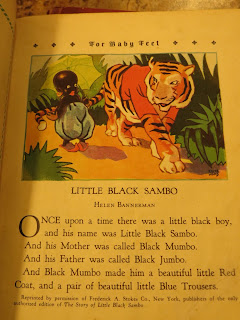

received a set of Book Trails. The

first volume, Book Trails for Baby Feet, begins with “Little Black Sambo,” a story told in many different

editions over the years and revived in three new versions not long ago. It’s a

story that’s been loved and hated and that has given rise to legends in which

some vague, powerful, conspiratorial “They” pull out all the stops to censor

children’s literature by making the story unavailable.

Here are a few facts from the

book world as I have come to know it.

·

Children’s books, read

over and over and not always treated gently, tend to survive in smaller numbers

than adult books, and a family of several children probably had no more than

one copy of a beloved book when the children were small. The likelihood of that

copy having survived is small.

·

Popular and well-loved

children’s books, like other published titles, usually go out of print over

time.

·

Why isn’t a popular book

reprinted? Most publishers of children’s books are conservative business

people. They do not want copyright problems, and they don’t want storms of

social protest -- unless the storms are going to sell books.

But also –

·

Every year publishers

are bringing out new titles for

children.

·

Illustration styles

change over the years, as do parenting methods.

·

Social awareness grows.

Does anyone think the Dick

and Jane readers fell victim to

censorship? Well, actually, a few people probably do think that, but evolving (or at least changing)

theories of education are a more likely explanation. As for why Dick and

Jane books and Little Black Sambo have commanded such high prices on the secondary

(i.e., not new) book market for as long as I’ve been selling used books, the

answer is simple: supply and demand. When people remember books from their own

childhood, want to get their hands on the books again, and the desired titles

are out of print and surviving copies in short supply, prices go up.

It is not a conspiracy. If

booksellers were that canny, we would all be rich.

But those who object to the

character of Little Black Sambo as depicted in the story have a serious point

to make. The little black boy in the pictures presents a stereotype, as does his name and the names of his mother and father, and so the

story fosters continued stereotypical thinking about darker races among young

white readers, while showing young readers of color nothing they can recognize

that relates to their own lives.

Growing social awareness is

obvious in another book that came to my hand recently, Bright April, by Marguerite di Angeli.

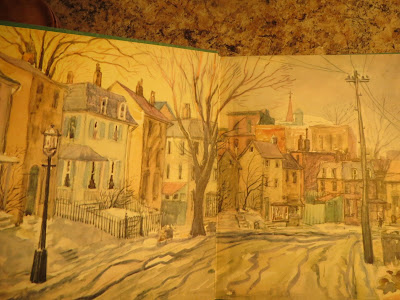

As soon as the book is

opened, the illustrated endpapers invite the reader into April’s world,

Philadelphia’s Germantown following the close of World War II. We learn that

she has a sister and two brothers, that her father is a postman, and that she

belongs to a Brownie troop.

In this mid-century African-American family, April helps her father clear

the sidewalk of ice and snow and helps her mother set the dinner table, always

trying to live up to the secret Brownie motto, “D.Y.B.!” There are hints of

difficulties to come when other little girls say unkind things or when April’s

serviceman brother (the year is 1946) writes home that he has been assigned to

laundry duty rather than given an architectural assignment for which he was

educationally trained and eager to execute. Today, perhaps, April’s parents

would give their children more emphatic, less gentle lessons, but de Angeli

certainly left “Little Black Sambo” behind.

And yet, simply comparing

these two fictional characters misses something else. “Little Black Sambo” and April

Bright are completely different kinds

of stories, just as “The Milkmaid and Her Pail,” by Aesop, another story in Baby

Feet, is entirely different from an

almost infinite number of realistic fiction for young people written in the 20th

century. Fairy tales such as “Cinderella” and “Snow White,” feminists point out,

gave starring roles to female stereotypes, not fully realized fictional girls

and women. And what about all the charming princes? Ever meet one in real life

who looked and talked and acted like the ones in fairy tales. And how about all

the wicked stepmothers?

In fairy tales and fables the

emphasis is on a simple plot, large actions, and lesson to be learned, while

realistic fiction, for readers of all ages, present an ambiguous world peopled

by distinct individuals trying to find their way in it.

In fairy tales and fables the

emphasis is on a simple plot, large actions, and lesson to be learned, while

realistic fiction, for readers of all ages, present an ambiguous world peopled

by distinct individuals trying to find their way in it.

Is there a place in our world

today for fables and fairy tales? That’s a serious question. I wonder what

others think. And where does contemporary YA dystopian literature fall with

relation to fairy tales and realism?

No comments:

Post a Comment