Our intrepid “Ulysses” reading group met three times to discuss the classic novel Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes. We read Edith Grossman’s recent and highly readable translation. Opinions on the work varied, but we were all glad we had made the glorious effort to reach that star of sixteenth/seventeenth-century Spain.

Don

Quixote

did not make its author rich. He was buried in an unmarked grave after a life

of military service, injury and disability, years of imprisonment and slavery,

extreme poverty, and a childless marriage. But he wrote Don Quixote, a work still read

over 400 years later. Little satisfaction to him that people in the 21st century, all over the world, are reading and laughing and being moved to tears by the tale, but, as we

say in our house, “He got his work done. He paid his rent in the universe.”

On

the morning after our final DQ discussion meeting, I came to the last page of a

much duller book, Beyond Life, by James Branch Cabell, a strange story –

more lecture, or at least essay, than story – in which one “character”

(Bartleby identifies “Charteris” as the author’s alter ego) supposedly

talks all night long to a friend who has dropped in to sit by his fireside.

When morning comes, the talker is dismayed to realize that his listener has

missed the entire point: the listener thinks Charteris has been talking about

how to write books, when all the while his real point was about life itself.

Charteris evinces, if you accept his point of view a thoroughly gloomy

assessment of life. All of us, beggar and pharaoh, are doomed to dust and

oblivion. Nothing will last. Thus, life is pointless. All our strivings, even

all our achievements. Pointless. Since life is pointless, however, we need a vision of life where what

we do makes sense, where our lives take on purpose, where the “glorious quest” does have some point.

This vision is the Romantic, and Charteris finds it not only in literature but

also in religion.

Chivalry

(to return to Don Quixote) was nothing if not romantic. Many claim

that romantic love was first conceptualized – even that it first began – with

the courtly love of the Middle Ages. Certainly

in the novel it is clear that Don Quixote has invented Dulcinea. Don Quixote’s

devotion to his ideal woman was founded on nothing more than his imagination

but gave him the necessary motivation to seek adventures and strive to be,

himself, a hero for the ages. In the end, he regains his senses and dies sane,

Dulcinea dropping out of the picture completely. Is all romantic love and all

striving to make the world better nothing more than self-deception? Is this the

message we are to take away from Cervantes?

I

was once accused, by a thorough-going skeptic, of “romanticizing my life.” My

country life, my old farmhouse, my romantic partner of decades (the love of my

life), my dream-come-true bookstore – all of it, the skeptic suggested, was

nothing more than a run-of-the-mill existence. Perhaps he even saw it as

somewhat shabby. James Branch Cabell, a.k.a. Charteris, would certainly see it

as pointless. My reply was that I had (and have) nothing to gain by giving

up my romanticism.

Why would I want to look objectively and cold-bloodedly on my one unique

passage through what others choose to see as a “vale of tears”?

There

were years, decades ago, when I despaired of making my dreams come true. Poorer

then than now, locked (or so it seemed) into a series of confining and

unsatisfying jobs that had nothing to do with the potential I felt within

myself, dissatisfaction making cruel inroads into the thrills of romance –

those were difficult times. I could not then imagine the life that lay ahead of

me: happy marriage, doctoral degree, literary life, country home. What seemed

impossible came to pass – certainly not without effort, but then, Don Quixote

did not sit home and wait for adventures to come to him, either.

The

thing is, if my romanticism is madness (as I put it to the skeptic), what have

I to gain by sanity? I still have unrealized dreams – literary and pastoral --

and am still reaching for them. “Crazy, he calls me. Sure, I’m crazy.” What else would you have me be?

But

now I come back again to Don Quixote and Cervantes, the author of the famous

knight-errant’s being. Don Quixote, dies “sane” at the end after his long

madness, renouncing chivalry and its impossible, bookish ideals. It would

hardly be surprising if Cervantes underwent a similar change of heart. After

all, what did he get for his life of service to king and country?

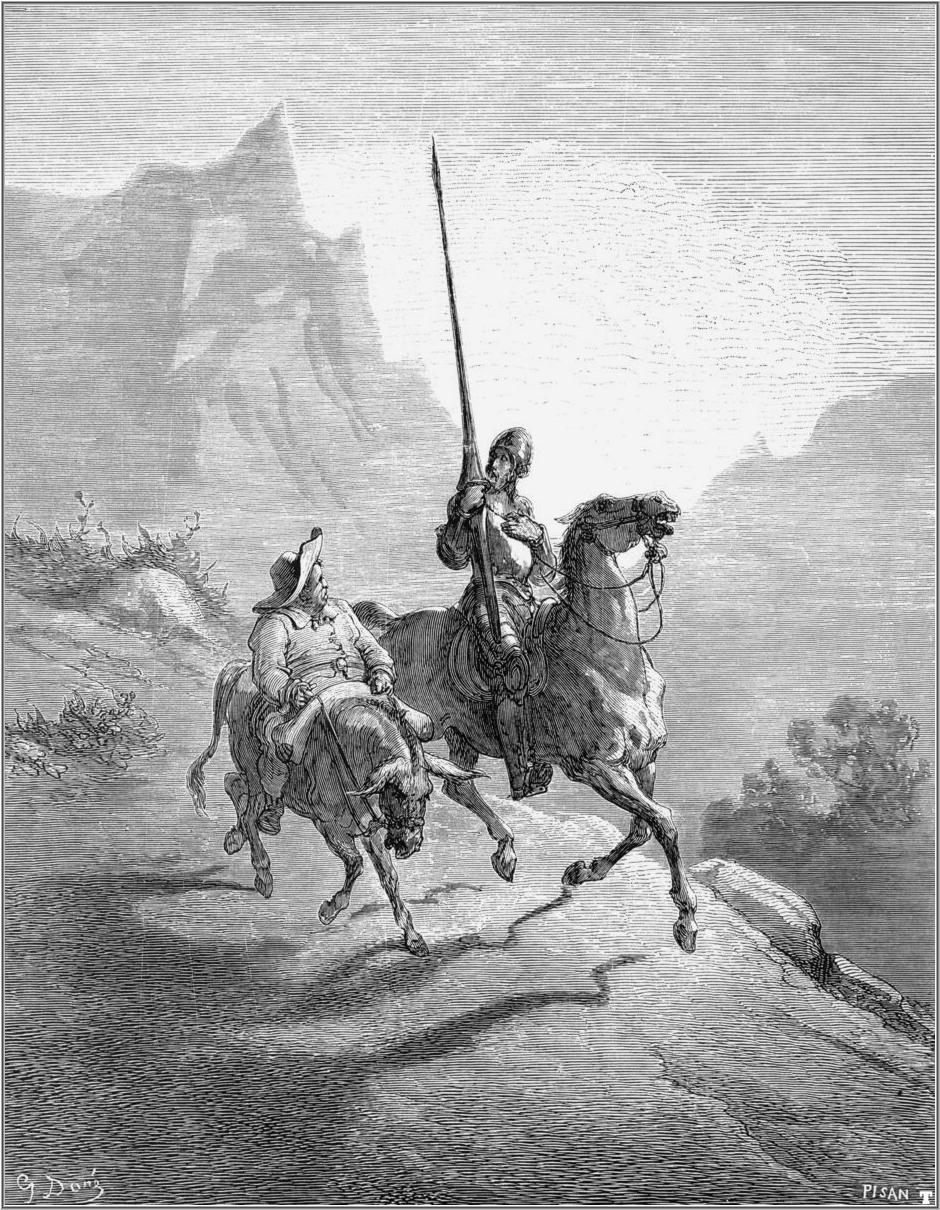

Ah,

but there is his glorious book! There is that wonderful figure of a skinny,

aging, deluded seeker of not only fame and glory but also just causes and

victory over cruelty and evil. A man with a noble quest!

Cervantes

knew whereof he wrote. What Don Quixote suffers in the legend, Cervantes

suffered in life, and yet he managed (pace Vladimir Nabokov, who was as

squeamish and offended by the novel’s violence as a Puritan would be over

modern passages of sexual content in literature) to make an amusing and

entertaining tale of it all. More importantly, we do not simply laugh at the

deluded would-be knight. We admire him. He lifts our spirits. Cervantes may

have been laid to rest feeling his life had been wasted, and that would be

sadder than the fictional knight’s return to sanity, because Cervantes was,

after all, a real man, but from our point of view he did not waste his time on

earth at all. He bequeathed to the entire world Don Quixote, a gentle, noble

soul, and thus he more than paid his rent in the universe.

I

am thinking about Cervantes and his gentle knight and remembering a teacher of

philosophy who spent his last days feeling he had wasted his life. Depressed in his final illness, he refused visitors and died, it would seem, an unhappy man.

And yet his students, of whom he had hundreds over the years, adored him! He

taught them how to think, how to question, how to value, and many looked back on

their classes with him as the most important of their time spent in college.

Maybe

it is not for anyone on earth to be the final judge of his or her own life.

Surely religion would remind us that we are not to be. But even the

nonreligious would perhaps do well to live as if their lives mattered, as if

what they do made a difference in the world – because it just very well might,

whether for one other person or for millions.

4 comments:

I think, I have to think, that everyone's life matters, that everyone makes a difference. But I also know that my work toward safer roads is highly romantic, That doesn't make me want to stop, though occasionally I do recognize the enormity of it all and that much of it won't get done in my lifetime. Still...I can't help but hope. If that makes me a romantic I'm OK with that. You're right. Being realistic wouldn't make me any happier.

Dawn, that's a perfect example. You are working to make the world better. One of the members of our reading group is involved in a charity, and someone asked her once, "When does it end?" The answer was that it doesn't --the need never ends -- but the work continues. Fighting the good fight continues. I'm glad you are working on truck safety, because it's important, and I would probably never have written the few letters I've written to legislators on the subject if you hadn't brought the issues to my attention.

Pamela...I know you are far too refined to steep to my level of coarseness, but it occurs to me that the old skeptic who used the term "romanticizing your life" as a pejorative was likely an asshole. I realize that is crass, so to soften the harshness of the comment, I will use the language of my Irish grandmother who might have called him an " arsehole", the "r" somehow rounding off the harsher edge of the term. In any event, he was a dick.

Those of us who are blessed to have a romantic vision of ourselves strive to fulfill a vision of our lives that completes us; hence the image of love, family, farm, literature, all the elements of fulfillment that are perhaps the next layer of life just above air, water, food, the basics of life. DQ was perhaps the most eloquent and articulate purveyor of the notion. It is impossible to imagine anyone creating such a masterpiece in a world of unfathomable commercialism but, I have decided that today is not the day to succumb to my usual cynicism and I will hold out hope for humanity. The romantic in me tells me its the right thing to do.

Dawn, I’ve been thinking more about the question of whether life is pointless because nothing will last forever or meaningful because each of us may be able to make some albeit temporary difference, and for me, the notion of life being meaningless because nothing humans do lasts for eternity is a meaningless objection. Who cares about billions of years from now? It is still short-sighted to think that our choices don’t matter, because they will certainly affect the generations that are already coming up to take our place, along with the world those generations will inhabit. We can be “romantic” enough to think and plan and act for the good of the next four generations, can’t we?

Greg, while we’re on the subject of people on whom romanticism is wasted, I ran across the most unbelievable story this morning, concerning the critics’ reception of the film version of “Man of La Mancha.” Time magazine (Wikipedia reports) “referred to the film as being ‘epically vulgar’ and called the song The Impossible Dream ‘surely the most mercilessly lachrymose hymn to empty-headed optimism since Carousel's "You'll Never Walk Alone."’” Talk about people without a sense of the romantic or any feeling for musical theatre! But then, a romantic like me would fall for a “mercilessly lachrymose hymn to empty-headed optimism,” wouldn’t I?

Post a Comment