As was true of his biography of John James Audubon, Gregory Nobles, in his new book, The Education of Betsey Stockton: An Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom, gives readers broad and deep insights into the time period of his subject and those parts of the United States in which she lived and worked. In a way, this approach was more necessary in writing of Stockton than of Audubon, since information about Stockton's life and work is fragmentary, and most of what survives was written by other people, but what it means for a reader is that we have a chance to be fully immersed in events and beliefs of our own American past while the author pieces together, like a quilt, the life of a specific historical human being.

Nobles as historian specializes in 19th-century America. In going beyond the life of his subject, his earlier biography of Audubon explored in detail the business practices and economics of that time, what it took to be considered a serious artist then, and the state of American art and science with relation to England and the European continent, as all these larger issues bore directly on the life of Audubon, who lived from 1785 to 1851.

Betsy Stockton, born into slavery, lived from around 1800 (exact date not known) to 1865. Given the color of her skin and the circumstances of her birth (the identity of her father can only be speculated), as well as her foreign missionary experience, long career as a teacher, and the fact that she lived through the Civil War and President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, larger national issues explored in relation to her life are slavery, racism, public education, 19th-century American politics, and the Civil War, along with the missionary movement of the time and the role of the town of Princeton, the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), and Princeton Theological Seminary in spearheading and shaping that movement for the Presbyterian church.

Since Stockton's unedited manuscript journal either did not survive her or has not yet come to light, only the published installments of her journal as edited by the Reverend Ashbel Green are available to account for her missionary travel to Hawaii in 1824-25, and while Green assured readers of the Christian Advocate that he made “very few corrections” to the letters before publication, there is no way of knowing to what extent he may have altered her original writing. Sadly, not many of her letters to Charles Samuel Stewart survive, either. But Nobles has brought together what scattered pieces of documentary evidence do exist, as well as the well-established basic facts of her life.

Stockton had been “given,” as an enslaved child, to Green’s wife, and it was Green himself, years later (Stockton was emancipated as an adolescent and afterward worked for wages in the household), who wrote a letter of recommendation for Stockton to Stewart. The latter was forming up a foreign mission to what were then known as the Sandwich Islands, and thus it was, author Nobles tells us, that Betsey Stockton was

…the first Black person, the first former enslaved person, the first single woman to serve as a missionary in Hawai‘i, and the first missionary to start an infant school for Black children in Philadelphia, the first name on the list of Black people leaving the main Presbyterian Church in Princeton to form a separate congregation, the first teacher in the only school for Black school in Princeton. Betsey Stockton lived a life of firsts, all of them in service to people of color.

Racism endemic to 19th-century, pre-Civil War Princeton, both the town and the college, should not be surprising but reads as shocking nonetheless. Black men defending their own wives from harassment were set upon by groups of rowdy white students, and Black parishioners of the Princeton Presbyterian Church were denied even their traditional separate gallery seating when a new building was constructed after the old church burned, as “the white Presbyterians pressed for separation,” and Black members were “dismissed” from membership. It was at that point in history that the First Presbyterian Church of Colour of Princeton was formed.

The College of New Jersey, with a high percentage of students from the South, attempted to remain “neutral” on the questions of slavery and secession right up to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, when

…several students climbed to the top of Nassau Hall to hoist an American flag, shout out some rooftop speeches, and fire a few old muskets as a show of support for the national government. This display was also an act of defiance toward the faculty, and particularly President John Maclean, Jr., who had sought to remain officially on the fence in the run-up to the rebellion. …His sympathy for southern boys led him to order the flag taken down, so as not to offend anyone who might see it as an institutional political statement. But in the context of open conflict, Maclean’s moderation had lost traction among northern students, and the flag went back up – and stayed there.

To read that the president of Princeton feared the American flag might offend some of his students and ordered it taken down astounded me. Those most likely to be offended would have been the Copperheads. (I would say that the Princeton & Slavery Project, so recently begun, is both long overdue and a good start.) And to think there are people in our country today who consider themselves patriots and fly the Confederate flag without fear of causing offense! Or perhaps they hope to offend? But let me not get sidetracked....

Throughout The Education of Betsey Stockton, the main subject herself never appears fully in sharp focus and technicolor, but that is not the fault of the author. Nobles could have written a novel and invented a character and put words in her mouth but chose not to do so, determined instead to hunt out “traces” of the real human being wherever he could find them. The Betsey Stockton who emerges from his research, though there is only a single photograph to give us some idea of her appearance, was a woman who “knew her own mind,” was “‘deliberate and dignified,” “certainly not weak willed,” someone who educated herself throughout her life and was respected by all who knew her. Given her intelligence, her sense of calling, and the racist environment in which she lived, it is hardly surprising that throughout her life Stockton knew occasional “low spirits.” In the end, however, more important than her spells of depression or discouraging events was her strength to go on doing good work, teaching children who might well never have had an education without her efforts.

Learning about one of the many “ordinary people doing extraordinary work” behind the grand stage of historical events is sufficient reason to read this book; another, however, is to examine in a different time period the racism that is such a deep stain on our country’s history and a painful legacy continuing in our own day. Political divisions, too, are nothing new to the never fully united United States, as this story shows so clearly, so in learning about Betsey Stockton’s life and work and the times she lived through we have yet another lens through which to examine our past – and we can never have too many of those.

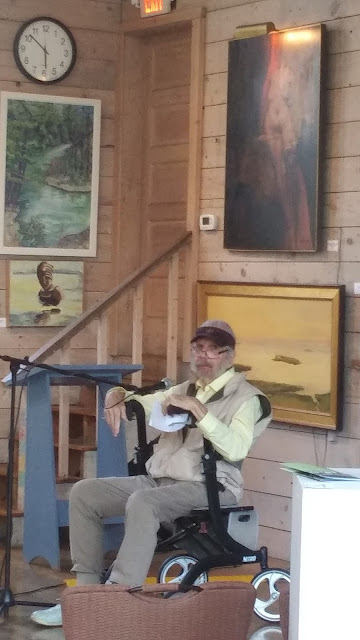

Greg Nobles will give a presentation at the summer library series on Tuesday, July 19.

The Education of Betsey Stockton: An Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom

by Gregory Nobles

University of Chicago Press

Hardcover, 292pp with notes and index

$25

Read since last listing:

56. Rumi, trans. by Kabir Helminski & Ahmad Rezwani. Love’s Ripening: Rumi on the Heart’s Journey (poetry)

57. Bowen, Rhys. The Venice Sketchbook (fiction)

58. Ashenburg, Katherine. The Mourner’s Dance: What We Do When People Die (nonfiction)

59. Davenport-Hines, Richard. Proust at the Majestic: The Last Days of the Author Whose Book Changed Paris (nonfiction)

60. Buzzelli, Elizabeth Kane. She Stopped for Death (fiction)

61. McMorris, Kristina. The Ways We Hide (fiction)

62. Nobles, Gregory. The Education of Betsey Stockton: An Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom (nonfiction)