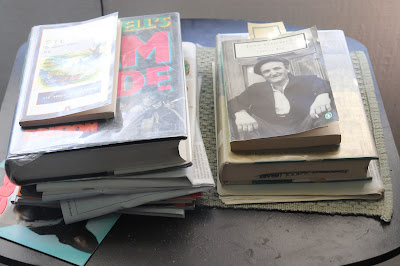

There is always time for reading, it seems. I’ve heard people who don’t find it so, but they have demanding fulltime jobs or immaculate homes with nothing out of place. Their concern for career or housekeeping translates, in my case, to a jealous guarding of my reading time. Much else, though, has fallen by the wayside in my life in recent months. Writing, drawing, new recipes, exercise (other than walking)....

Writing, primarily: sadly neglected! I manage to get a blog post together now and then and to write letters to friends, but my Silas project, part of each morning, has been on the back burner now for – how long? Here is the last time I wrote anything related to Silas, this chapter of mine the first with not a word transcribed from Silas’s diary:

Chapter Seventeen

A Week Without Silas

2/5/2021, 10:20 a.m.

Reading now The Great Hunger, Cecil Woodham-Smith’s history of the Irish famine, a book that did not come into my hands purely by accident. When we learned that the Friends of the Library bookstore over in Sunsites (Pearce) was open to the public on Monday, though the library itself was offering only curbside service, we made that our destination and spent $25 between us on books, worth much more to us than the bargain prices we paid.

It was a couple of Silas’s throwaway lines in January and the first of February that sent me looking for material on mid-century Ireland. His remark about being “tickled” when the Irishman was disappointed to find American equality more myth than reality was the first nudge. The second was his choice of the Know-Nothings as a topic in his newly formed debate society.

The 19th-century movement called the Know-Nothings began as a secret organization (any member asked about it was instructed to say, “I know nothing”), their anti-immigration and virulently anti-Catholic position a response of fear and resentment to the flood of 1840s immigrants from Ireland and Italy. Is it any surprise that the foremost leader and first martyr of this cause also found women’s suffrage an abhorrent and unnatural idea? The Know-Nothings’ nativism found plenty of support among elected officials as well as among a white working class, and what began in secret as the Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB, formed in 1849) soon morphed into the very public – and briefly very successful -- American Party, the first serious third-party challenge in American politics. Between 1852 and 1854 they won elections at every level. The party split soon afterward, however, over the issue of slavery, a matter even more incendiary than immigration.

The situation in 1840s Ireland had been unlike anything every known in the United States, starving Irish sheltering as best they could in muddy ditches after being evicted from cottages they themselves had often built, improving the land they rented to the profit of their landlords. Many in England believed reports of the potato famine to be a “false alarm,” the “invention of agitators” – in other words, what our recent former president would have called “a hoax” and “fake news.”

It was no hoax. Since deaths went unrecorded, with uncounted numbers literally dying of starvation in the open, there is no way to arrive at a precise figure for the tragedy, but population numbers between 1841 and 1851 show a drop of two and a half million. Allowing for the roughly one million Irish who emigrated during the years 1846-51, this puts the death toll from starvation at approximately a million and a half. At first there were attempts at public relief, as well as a long effort made by the Society of Friends (Quakers) to save lives, but in the third and fourth year of the famine soup kitchens were closed, government work projects stopped, and the government in London held to a strictly laissez-faire policy, saying the Irish must help themselves. They were told to collect taxes -- in a land of bankruptcy and financial ruin, where no one any longer had the ability to pay taxes – and to provide locally for the relief of the destitute.

Nor was starvation the only plague on Ireland during those years. Typhus and cholera contributed to the tragedy, spread all the more rapidly in workhouses, soup kitchens -- and on ships. As there looked to be no future for the Irish in their own land, those who were able sought to leave by any means possible. Passage to Canada was cheaper (some sold all they had; others had fares paid by landlords eager to be rid of them) than passage to the United States and entry into Canada easier, but most Irish had no wish to remain any longer under the flag of England, and so the vast majority who landed in Canada and survived crossed the border to the United States as soon as possible.

Such was the background in Ireland that led to the most massive emigration ever from any European country – and the entry into the young United States of vast numbers of desperate, unskilled immigrants, eager and willing to work for almost any wage offered. Such was the wave of a population movement that created fears triggering the rise of nativism and unsurprising political opportunism, much like what we have seen again in recent years a century and a half later.

So now, as you see, it has been over a month for me without Silas, a month that has flown by. The nineteenth century, recently so immediate in my thoughts, has receded to a far and misty horizon.

Last Saturday a group I call “ghost town ladies,” a group the Artist refers to as “your coven” and the ladies self-reference as “the riff-raff” met for lunch for the first time in well over a year. A red-letter day, long awaited! The following Monday the Artist and I drove to Benson to rendez-vous with Leelanau friends currently spending a couple of months in Tucson. Another lunch date! In both cases, all had had their double doses of vaccine. But I cannot blame those welcome distractions for my neglect of Silas.

No, it’s all the darn little dog, little Peasy, that stray from the pound, whose training and domestication has so absorbed my daily attention and focus. He has come such a long way! Given a full year…. But I don’t have a full year, only another couple of months, at most, and little Pea, while madly in love with me and tentatively fond of the Artist, is still afraid of almost everyone else. A bookstore future for this dog is the most unlikely scenario.

What is his likeliest future? I’m still working on figuring that out, but while he is in my care I work daily on lessons to civilize the little love-bug.

Silas is long dead, and Peasy is very much alive. No one other than me cares if Silas’s diary is every transcribed, and hordes of more qualified writers than I have written of 19th century America. But Peasy was ignored and passed over for three months in the pound in Safford. And – he loves me. He cares!

While Peasy distracts me from writing and much else, though, he also focuses my immediate attention and gives purpose to my days. The progress we have made together gives me a sense of accomplishment and deep satisfaction. Besides that, he is my daily companion in rambles over the range, out in the sun and the wind and the dust.

“How was it?” the Artist asks when the dog and I return to the cabin, tired and thirsty and happy.

“It was great!”

We’re here now. That has been my mantra for years, wherever I am: we’re here now. And I don’t want to miss being here.